The Truth About Lady Godiva

Uncovering Godiva

NO other early Englishwoman has been remembered as long, or as provocatively, as Lady Godiva. The name instantly conjures an image of a woman on horseback, clad only in her hair. Whether depicted in a 15th century print or gracing a modern chocolate box, Godiva lives – and rides – on in our imaginations.

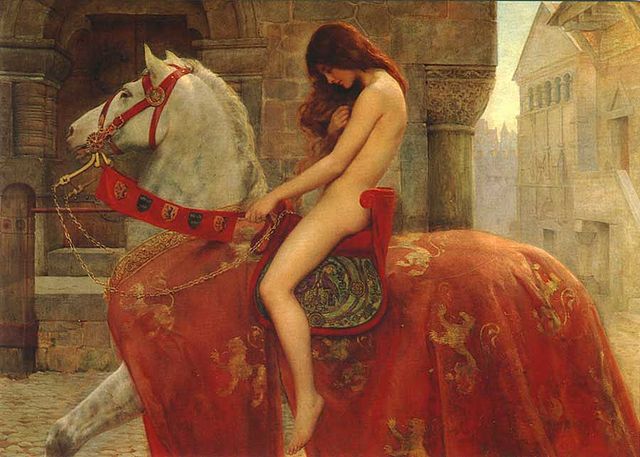

Lady Godiva by John Collier: An abashed young maiden.

Godiva is the latinised form of the Old English name Godgyfu or Godgifu (literally, “God’s gift” or “good gift”). Godgyfu was an 11th century Anglo-Saxon aristocrat whose life spanned one of the most tumultuous periods in early English history. Despite her illustrious husband, renowned piety, and religious benefactions, without the tantalising legend of her ride through the Midlands town of Coventry she would likely be completely forgotten.

What is known of Godgyfu is found in the chronicles of various religious foundations, mentions of her or her husband in charters, and the post-Conquest compilation known as the Domesday Book. The first positive record of her is in 1035, when she was already married to Leofric, Earl of Mercia. Her birth date is unknown. Similarly, the date of her ride through Coventry cannot be known, possibly it was linked to the dedication of the Priory she and Leofric built there in 1043.

Here I must also acknowledge that despite records dating to the late 12th century concerning her ride, there are some modern scholars who doubt that it ever took place. I am persuaded that it did.

To return to fact: Like other Anglo-Saxon women of her class, Godgyfu owned property in her own right, both given to her by her parents and acquired through other means – gifts from her husband, inheritance from relatives, and purchases and exchanges from individuals and religious foundations. The modest farming village of Coventry was one of them. The Domesday Book lists it, twenty years after her death, as having sixty-nine families.

It is not known why Godgyfu and Leofric turned their attention to Coventry, which after all, was a small and seemingly unremarkable farming community. As early as 1024 Bishop Æthelnoth (later to be Archbishop of Canterbury) gave to Leofric a priceless relic, the arm of St.Augustine of Hippo, which had been purchased by the bishop in Rome and which he apparently indicated was intended – we do not know why – for Coventry.

The response of Leofric and Godgyfu was to create a suitable sanctuary to house this exceptional relic. The lavishly decorated Benedictine Priory of St.Mary, St.Osburgh, and All Saints was dedicated by Archbishop of Canterbury Eadsige in 1043, on property owned by Godgyfu. Within was a shrine to St. Osburgh (a local holy woman who had earlier founded a nunnery in Coventry) which held her head encased in copper and gold. St.Augustine’s arm took its place in a special shrine, and Godgyfu and Leofric also presented to the new Priory many ornaments of gold, silver and precious stones, so that it was famed for its richness. Leofric further endowed the Priory with estates in Warwickshire, Gloucestershire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, and Worcestershire.

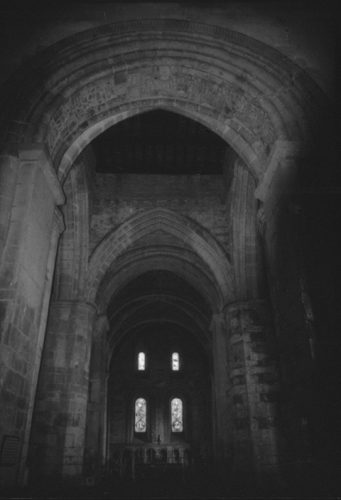

Their religious endowments were many, restoring, enriching, or founding houses in Much Wenlock, Worcester, Evesham, Chester, Leominster, and Stow in Lincolnshire. This last, the Priory Church of St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey, is of particular interest as a significant portion of the beautiful and impressive extant church there issued from their hands. The earliest stonework in the church dates from 955; Godgyfu and Leofric greatly endowed and enriched it from 1053-55. The lofty crossing features four soaring rounded Saxon arches (which now enclose later pointed Norman arches built within the original Saxon arches). A 10th or 11th century graffito of an oared ship is scratched into the base of one of the Saxon arches, possibly a memento from a Danish raider who sailed up the nearby Trent.

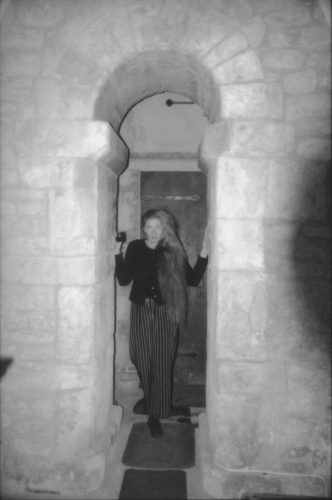

The north transept houses a narrow, deep Saxon doorway of honey-coloured stone, which would originally have been lime-washed and over-painted with decorative designs. It likely led to a chapel in Godgyfu’s day, and surely she passed through this very arch. To experience St. Mary’s Stow, built just ten years after the dedication of the Coventry church, is to begin to imagine what the Priory Church of St. Mary, St Osburgh, and All Saints may have been like.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey, a 10th c church endowed by Godgyfu and Leofric in the mid-11th c. Note the three windows in the transept, shown below from the interior.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. Three windows, three ages. The circular window is Saxon; the very narrow round-headed one beneath it is Norman; the larger pointed one later Medieval. |

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. The crossing. The later, pointed Norman arches were actually built within the larger rounded Saxon ones. |

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. North transept. Narrow Saxon doorway with your author inserted for scale. |

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. Ancient stone steps to tower. |

Leofric was a man of considerable talent and statesmanship; no man could survive forty years as Earl without these qualities. Elevated to Earl (a title and position new to the English, replacing and expanding the Anglo-Saxon ealdorman) in 1017 by the Dane Cnut, he survived and thrived through Cnut’s reign. Then followed that of Harold Harefoot (1035-1040), in whose selection as successor to Cnut Leofric was instrumental. Hardacnut, Cnut’s other son, reigned next (1040-1042), and then began Edward the Confessor’s rule (1042-1066).

Unsurprisingly for his age, Leofric could alternate between great rapacity and great piety, his depredations and subsequent generous benefactions upon the town of Worcester being a case in point. In 1041, when Hardacnut was king, two of his tax collectors were murdered by an angry and over-taxed group of Worcester citizens.

An act of this nature, upon the direct representatives of the king, was seen as almost an assault upon the king’s body itself. In reprisal Hardacnut ordered Leofric to lay waste to Worcester, which Leofric did with complete and horrifying efficiency, made perhaps even more reprehensible as Worcester was the cathedral city of his own people. Afterwards (and seemingly as personal reparation) Leofric bestowed many gifts of treasure and lands upon the religious foundation there, enough to ensure that his memory would be revered and not reviled.

He seems to have been successful in this. Near the end of his life Leofric experienced four religious visions which were carefully recorded by the monks at Worcester and published after his death in 1057. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1057 noted,

“…In this same year, on 30 October, Earl Leofric passed away. He was very wise in all matters, both religious and secular, that benefited all this nation. He was buried at Coventry, and his son Ælfgar succeeded to his authority…” (G.N. Garmonsway translation)

Following his death, Godgyfu made additional gifts to the religious foundation at Worcester to aid in the repose of Leofric’s soul and for the benefit of her own. These gifts included altar frontals, wall hangings, bench covers, candlesticks, and a Bible, and joined a long list of items and estates the two had granted to Worcester in the years prior to Leofric’s death.

Leofric and Godgyfu had one known child, the above-mentioned Ælfgar, who died in 1062. His daughter Ealdgyth was wed briefly first to a Welsh king and following his death, to Harold Godwineson, killed by William of Normandy’s men on the field at Hastings. Thus for nine months Godgyfu was grandmother to the queen of England.

Godgyfu died in 1067, the year following Hastings. At her death she was one of the four or five richest women in England with estates valued at £160 of silver. Her lands were then forfeit to new king William.

Godgyfu was buried next to her husband in the Priory church in Coventry they had created. According to chronicler William of Malmesbury, her dying act was characteristically pious: as a final gift to the Priory, she ordered hung about the neck of a statue of the Virgin Mary her personal rosary of precious stones. (The church was alas, destroyed like so many others during the Reformation, the treasures looted and dispersed.)

Godiva: Her Literary Legend

Maureen O’Hara as Godgyfu: read on to see why I think this image is the closest to the truth…

IN the first part of this essay I stated that I was convinced that Godgyfu had in fact enacted her famous ride. Now we will examine the way her ride has been remembered through the ages in poetry, prose, and visual art, and then look at why she may have performed such an extraordinary act, what it meant, and how that meaning has been perverted over time.

Over the centuries the story of Godgyfu’s ride has enjoyed a life of its own. This is the oldest surviving account of it:

The Countess Godiva devoutly anxious to free the city of Coventry from a grievous and base thralldom often besought the Count, her husband, that he would for love of the Holy Trinity and the sacred Mother of God liberate it from such servitude. But he rebuked her for vainly demanding a thing so injurious to himself and forbade her to move further therein. Yet she, out of her womanly pertinacity, continued to press the matter insomuch that she obtained this answer from him: “Ascend,” he said, “thy horse naked and pass thus through the city from one end to the other in sight of the people and on thy return thou shalt obtain thy request.” Upon which she returned: “And should I be willing to do this, wilt thou give me leave?” “I will,” he responded. Then the Countess Godiva, beloved of God, ascended her horse, naked, loosing her long hair which clothed her entire body except her snow white legs, and having performed the journey, seen by none, returned with joy to her husband who, regarding it as a miracle, thereupon granted Coventry a Charter, confirming it with his seal.from the Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover (d. 1236), translated from the Latin by Matthew of Westminster c 1300-1320

Later chroniclers embellished and expanded upon the legend:

But Gaufride sayth that this gentle and good Lady did not onely for the freeing of the said Citie and satisfying of her husbands pleasure, graunt vnto her sayde Husband to ryde as aforesayde: But also called in secret manner (by such as she put speciall trust in) all those that then were Magistrates and rulers of the said Citie of Couentrie, and vttered vnto them what good will she bare vnto the sayde Citie, and how shee had moued the Erle her husband to make the same free, the which vpon such condition as is afore mencioned, the sayde Erle graunted vnto her, which the sayde Lady was well contented to doe, requiring of them for the reuerence of womanhed, that at that day and tyme that she should ride (which was made certaine vnto them) that streight commaundement should be geuen throughout all the City, that euerie person should shut in their houses and Wyndowes, and none so hardy to looke out into the streetes, nor remayne in the stretes, vpon a very great paine, so that when the tyme came of her out ryding none sawe her, but her husbande and such as were present with him, and she and her Gentlewoman to wayte vpon her galoped through the Towne, where the people might here the treading of their Horsse, but they saw her not, and so she returned to her Husbande from the place from whence she came, her honestie saued, her purpose obteyned, her wisdome much commended, and her husbands imagination vtterly disappointed. And shortly after her returne, when shee had arayed and apparelled her selfe in most comely and seemly manner, then shee shewed her selfe openly to the peuple of the Citie of Couentrie, to the great joy and maruellous reioysing of all the Citizens and inhabitants of the same, who by her had receyued so great a benefite.

from the account of Richard Grafton (d.1572) M.P. for Coventry

The introduction of the voyeur famously to be known as Peeping Tom is even more recent, a 17th century embroidery:

…In the Forenoone all householders were Commanded to keep in their Families shutting their doores & Windows close whilest the Duchess performed this good deed, which done she rode naked through the midst of the Towne, without any other Coverture save only her hair. But about the midst of the Citty her horse neighed, whereat one desirous to see the strange Case lett downe a Window, & looked out, for which fact, or for that the horse did neigh, as the cause thereof. Though all the Towne were Franchised, yet horses were not toll-free to this day.

from the account of Humphrey Wanley (1672-1726)

It was left to Alfred Lord Tennyson, in 1842, to codify the tale into the form in which it became known around the world.

Lady Godiva by Edmund Blair Leighton, 1892. At her moment of decision as described in the Tennyson poem.

Godiva

I waited for the train at Coventry;

I hung with grooms and porters on the bridge,

To watch the three tall spires; and there I shaped

The city’s ancient legend into this:-

Not only we, the latest seed of Time,

New men, that in the flying of a wheel

Cry down the past, not only we, that prate

Of rights and wrongs, have loved the people well,

And loathed to see them overtax’d; but she

Did more, and underwent, and overcame,

The woman of a thousand summers back,

Godiva, wife to that grim Earl, who ruled

In Coventry: for when he laid a tax

Upon his town, and all the mothers brought

Their children, clamouring, ‘If we pay, we starve!’

She sought her lord, and found him, where he strode

About the hall, among his dogs, alone,

His beard a foot before him and his hair

A yard behind. She told him of their tears,

And pray’d him, ‘If they pay this tax, they starve.’

Whereat he stared, replying, half-amazed,

‘You would not let your little finger ache

For such as these?’ – ‘But I would die’, said she.

He laugh’d, and swore by Peter and by Paul;

Then fillip’d at the diamond in her ear;

‘Oh ay, ay, ay, you talk!’ -‘Alas!’ she said,

‘But prove me what I would not do.’

And from a heart as rough as Esau’s hand,

He answer’d, ‘Ride you naked thro’ the town,

And I repeal it;’ and nodding, as in scorn,

He parted, with great strides among his dogs.

So left alone, the passions of her mind,

As winds from all the compass shift and blow,

Made war upon each other for an hour,

Till pity won. She sent a herald forth,

And bade him cry, with sound of trumpet, all

The hard condition; but that she would loose

The people: therefore, as they loved her well,

From then till noon no foot should pace the street,

No eye look down, she passing; but that all

Should keep within, door shut, and window barr’d.

Then fled she to her inmost bower, and there

Unclasp’d the wedded eagles of her belt,

The grim Earl’s gift; but ever at a breath

She linger’d, looking like a summer moon

Half-dipt in cloud: anon she shook her head,

And shower’d the rippled ringlets to her knee;

Unclad herself in haste; adown the stair

Stole on; and, like a creeping sunbeam, slid

From piller unto pillar, until she reach’d

The Gateway, there she found her palfrey trapt

In purple blazon’d with armorial gold.

Then she rode forth, clothed on with chastity:

The deep air listen’d round her as she rode,

And all the low wind hardly breathed for fear.

The little wide-mouth’d heads upon the spout

Had cunning eyes to see: the barking cur

Made her cheek flame; her palfrey’s foot-fall shot

Light horrors thro’ her pulses; the blind walls

Were full of chinks and holes; and overhead

Fantastic gables, crowding, stared: but she

Not less thro’ all bore up, till, last, she saw

The white-flower’d elder-thicket from the field,

Gleam thro’ the Gothic archway in the wall.

Then she rode back, clothed on with chasity;

And one low churl, compact of thankless earth,

The fatal byword of all years to come,

Boring a little auger-hole in fear,

Peep’d – but his eyes, before they had their will,

Were shrivell’d into darkness in his head,

And dropt before him. So the Powers, who wait

On noble deeds, cancell’d a sense misused;

And she, that knew not, pass’d: and all at once,

With twelve great shocks of sound, the shameless noon

Was clash’d and hammer’d from a hundred towers,

One after one: but even then she gain’d

Her bower; whence reissuing, robed and crown’d,

To meet her lord, she took the tax away

And built herself an everlasting name.

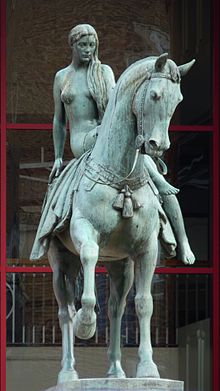

Oh, the everlasting shame! 19th century sculpture

by John Thomas, Maidstone Museum, Kent.

All of these accounts ignore important facts and are fraught with inconsistency and illogic. Coventry at the time of the ride is depicted not as a small village but as teeming metropolis (recall that twenty years after Godgyfu’s death it had less than seventy families). There is no corroborating evidence to suggest that Leofric warranted the reputation of a husband who would order his virtuous wife to parade naked through town in an attempt to humiliate her at worst, or at best to prove the sincerity of her compassionate leanings. On the contrary, the long record of the joint benefactions of Godgyfu and Leofric indicate that theirs was a marriage of more or less equal tastes and aims.

Divorce was far from uncommon amongst Anglo-Saxon aristocracy; if Godgyfu had found herself in an untenable marital situation the union could have been speedily dissolved, with her retaining all the property she had brought into the marriage and custody of any minor children. Thus separation from a husband who exhibited abusive behaviour could be accomplished without undue economic hardship upon the departing wife.

But by far the most vital fact ignored in these retellings is that Godgyfu possessed the village of Coventry outright. She need not ask Leofric or anyone else to suspend or repeal any tax or toll upon it, as she controlled the collection of these herself. The sole exception was the heregeld, an onerous levy instituted by Cnut to pay for the king’s personal body-guard. Until revoked by Edward the Confessor in 1051, it was a national tax, required of all. Godgyfu would not have been able to suspend it – but she certainly could have paid it from her own purse.

The reason for this persistent misrepresentation is simple, but profound in its implications to the unfolding of the tale. Because Anglo-Saxon woman — indeed all women in England — had by the time of even the earliest extant retelling lost the extensive property (and other personal and legal) rights they had enjoyed prior to the disaster of 1066, chroniclers wrote from the perspective of Norman law and mores.

As the tale became sentimentalized and ever-more erotically charged, the victimization of Godgyfu became paramount – she must become a virtuous victim, compelled by an unfeeling husband to perform (in the chronicler’s eyes) a humiliating act, in a Coventry subjected, as was she, to his utter domination. There is no room in these later recountings for a woman of independence and intelligence, acting out of deep-seated devotion, and inspired by well-remembered (and in some instances, still enacted) pre-Christian agricultural rituals and Biblical acts of religious dedication and contrition.

I believe her ride was performed as an act of religious devotion and contrition, and that it was inspired by examples of both heathen and Christian ritual, including sacred nakedness. The devotion was rooted in her real and demonstrable piety and her many benefactions (some of them jointly made with Leofric) to various religious foundations, including building a stone church in Coventry, which they enriched with a shrine to a local martyr, the nun Osburgh, who had been killed in a Danish raid in Godgyfu’s lifetime. The extraordinary relic of the arm of St Augustine of Hippo was also given a home in that church.

We forget how close to the bone our heathen background was back then; there was a tremendously rich mixing of heathen ritual and magic combined with Christian worship. One well-known ritual, preserved in the British Library, is called in Old English Æcerbot, or Field Remedy. It is a heady combination of patently heathen practice (herb craft, charms, magical signing, the calling out to Mother Earth) and Christian ritual (the Latin Mass, participation of a priest) and is typical of the Anglo-Saxon era. For examples of sacred nakedness, the ritual bathing of the Old Saxon Earth Goddess Nerthus, responsible for all fruitfulness, was recorded by the Roman historian Tacitus, and on the Christian side there were many, many depictions of the repentant Mary Magdalen and St. Mary of Egypt, clothed only in their hair.

Her ride could also represent an act of referred contrition, as a particular response to her husband’s destruction of Worcester. You will recall that Worcester was actually Leofric’s own property, but that at Hardacnut’s order following the killing of two tax collectors there Leofric carried out a complete harrowing of the town. He simply destroyed it, even the church, and left not one grain barn standing.

So if Godgyfu relieved the residents of Coventry by paying the heregeld tax from her own purse, and then followed it with a miniature pilgrimage on horseback to the site where a revered holy woman, Osburgh, had been martyred – a site where she would soon build an impressive stone church, laden with treasure – these acts would have been remarkable enough to ensure her memory be preserved in the tiny and heretofore unimportant hamlet of Coventry.

Despite – or because of – the perverting of the tale, it grew. But however obscured, its underpinnings remain sound. As Joan C. Lancaster, former City Historian of the City of Coventry, states in her definitive study, Godiva of Coventry, the legend was predicated on a

“genuine local tradition known to the Coventry people in the 12th century…It was based on memory of her piety and her share in atoning for her husband’s sins, and also the removal of the heregeld when she was ruling over them.”

It is this Godgyfu I choose to celebrate and honour.

An unashamed Godgyfu.

Scultpure by Sir William Reid Dick,

1949 in Broadgate, Coventry

Godiva of Coventry, Joan C. Lancaster, Coventry Corporation, 1967

Lady Godiva: Images of a Legend in Art & Society, Ronald Aquilla Clarke and Patrick A.E. Day, City of Coventry, 1982 (pamphlet)

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, G. N. Garmonsway, trans., J.M. Dent & Sons, 1975

Domesday Book, Thomas Hinde, editor, Coombe Books, 1996

The Beginnings of English Society, Dorothy Whitelock, Penguin, 1974

In addition Prof. Daniel Donoghue of Harvard University graciously allowed me to review several chapters of his manuscript, which was published as Lady Godiva: A Literary History of the Legend, Blackwell, 2002.

My novella Ride is the story of Lady Godiva.

I so enjoyed this. I recently learned that I am a descendant of this remarkable woman. I can visualize her entreating her husband on behalf of the people and him laughing at her while saying he would lower the taxes when she rode naked through the town. Maybe he underestimated her. Put in the context of the times, you are most likely closer to the truth. Thank you.

no way then we are somehow related, i am also a descendant of hers

In researching the earliest Banastre family links in Normandy pre-conquest, I found Godifu as the granddaughter of the Count de Corbiel or William ‘the Warling” from Normandy France- (William the Conquerer’s ‘ half ‘ brother) and her uncle was the Bishop of Bayeaux, Odo.

From family study in Coventry I found : Thurstan Banastre was her nephew as Robert de Banastre was her brother by Regnault de Corbeil, son of the Warling. Regnault was known to marry a ‘ great princess of Northumberland’ and was known to visit the area- when William the conquerer banished him -to remove anyone who could challange him to the throne. He went to the Norman stronghold in southern Italy, Calabria and his friend Duke Robert de Guiscard.

Extract : [The village of Allesley had no church before the 1140s, it being a part of the property of St Mary’s Priory, Coventry, which was founded in 1043 by Earl Leofric and his wife Lady Godiva, another relative of William the Warling. During the civil wars of Stephen and Matilda (1140s), Thurstan Banastre, lord of Allesley under the Earl of Chester, petitioned for a chapel of ease for baptisms and marriages – as well as a place of sanctuary for villagers caught up in the fighting around Coventry.]

These Banastre’s were the barons of Newton and managed 19 villages in the area at that time – as companions of the conquerer- going from Normandy to Lancashire by way of Prestatyn castle in Wales. 1167 saw them fleeing Conan and many others, who ‘ threw down their castle.’

The Banastre’s arrived with hundreds of their Welsh villagers, known by parliament for at least 100 years as ” Westeroys of Warin Banastre.”

Cheers

Debra

Thanks for writing, Debra, about your very interesting family research. I’m glad you found my essay, and hope you read my novella, Ride, which you might enjoy.

You could definitely see your enthusiasm in the work you write.

The sector hopes for more passionate writers such as

you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

Many thanks Meagan. Being true to my own vision is the way I have arrived where I am; thank you for singling that out. I hope you will go on to read The Circle of Ceridwen Saga, Book Five of which will be released shortly…

I have not so much knowledge of English history, but I am studying the old Danish genealogy, and somewhere in the puzzle I would like to put the Lady Godiva as a descendant of the Danish viking daughter Gunhild, sister of Svend Forkbeard, the children of Harald Bluetooth. But but – I still need to find more indications that this could be so. They were a fierceful family and I can easily imagine a woman from this bloodline making such a protest. And of course Prima Nocte is so shamefull that it easily would be kept a secret, even in legends from the past… camouflaged in (as you almost say) a ridiculous tale (consideringer Godivas status) about taxes.

Short about Danish Gunhild: She was married to ‘Auti’ the Moneyer of Lincolnshire, and died in the attack of Danelaw 1002. Her sons bore the title ‘Thegn’ meaning ‘saxon noblemen’. One of them (Toke Trylle) became an important ‘hövdsmand’ (Danish version of an ealdorman) close to the Danish king. Some other genealogists have her married to Pallig Tokesen, Ealdorman of Devonshire – this could perhaps have been her first marriage. If I ever find my ‘proof’, I’ll get back to you 😉

Great page ! Thank you for this and for replying to my comment.

All fascinating work, MS and I commend you for taking it up. If you read my novella “Ride” it gives my explanation for her act….and as you know from reading my essay here, her story had been so corrupted over the centuries that merely educating people about the legal status of women in Anglo-Saxon England must be done before one can begin to sort the likely from the highly improbable. See my essay on this site https://octavia.net/womens-rights-anglo-saxon-england/ for more about that. Thank you for your intelligent and interesting comments!

Where were you able to find that Auti the moneyer of Lincolnshire was married to Gunhild?

Did you ever consider that the famous ride could have been a protest against Prima Nocte ??

Thank you MS for your thoughtful question. Prima Nocte was the supposed “right” of a lord to the first night with a woman prior to her marriage. There is no evidence it was practiced in Anglo-Saxon England, and in fact reports we have of this practice are from later centuries (and often times France). Leofric was many things, but not a philanderer. And divorce was readily available to Anglo-Saxon women; if Leofric had been serially unfaithful to Godgyfu she would have sought one. It was only after Hastings that English women lost easy access to divorce, along with their property rights.