The Importance of Sheep

I stroked one of the wound balls of yarn, and thought of all the good things of sheep: milk, and cheese, and greatest of all, wool; and I thought too of the making of parchment, and that without a lambskin I could not make any, and so could not send to Ælfwyn’s parents the letter I had promised.

She seemed to read my thoughts, for she said, “Can it be true that no sheep are left here? How will the people live without sheep? How even will we live? If the Danes are to stay here and make Lindisse their home, surely they know they must farm and raise sheep.”

The Circle of Ceridwen, Chapter the Twenty-fifth: The Weaving of Life

Milking an ewe. Sheep’s milk and cheese was a valued commodity for hundreds of years.

Life without sheep was unthinkable. For the average Anglo-Saxon, sheep meant sustaining meat, milk, and cheese, healing wool-wax, valuable parchment, and most vitally, fleece. Fleece to be shorn or pulled, and spun and woven into cloth. Recall that there were then only two types of fabrics: woolen ones, and linen. (Only the very rich, on rare, ceremonial occasions, clothed themselves in imported silks.)

It is not for nothing that the seat of the Lord High Chancellor in the House of Lords has been a woolsack.

The woolsack is the low cushion (with protruding backrest in middle) facing the throne in this photograph of Westminster, c 1880.

Wikimedia Commons

It is almost impossible to overstate the importance of sheep on the early economy:

The history of the change from mediaeval to modern England might well be written in the form of a social history of the English cloth trade.

G.M. Trevelyan, O.M., Illustrated History of England

Sheep can thrive in harsh and stony environments where crop farming is difficult, and if protected from natural predators small flocks can rapidly grow large due to many ewes’ propensity to twinned lambs. Raw wool was exported from England to the Continent at least by the 8th century, and greatly expanded under Norman rule. British wool found eager buyers abroad, especially for the productive looms of Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres – creation site of so many magnificent medieval tapestries. The vast majority of exported wool went into durable cloth for clothing and drapery use – cloth sent back to the British Isles in its finished state.

It was Edward III who, by inviting skilled Flemish weavers to settle in England in 1331, began to reverse this wool-out/cloth-back trade. Many of the Flemings were in fact English allies and refugees from the Hundred Years War. Although subject to discrimination, suspicion, and even outright massacre in the London uprising against them in 1381, these weavers became entrenched in English society, their skill elevating the woollens trade to an exalted economic status.

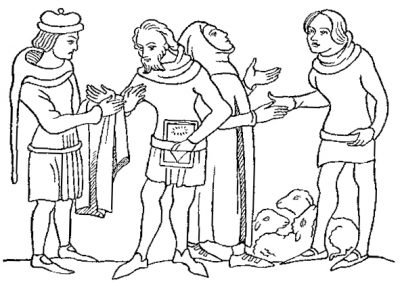

Buying and selling sheep. Having reached an agreement, two men shake hands.

Of the sixty-five distinct sheep breeds in Britain today, the oldest is the Soay, a descendent of the animals brought by the earliest Neolithic immigrants. A remnant population still lives on the St Kilda islands off the Outer Hebrides. They are typically brown, black, or cream-coloured, with white bellies, and both ewes and rams have downward curving horns. Their wool is fine and short (2″).

Soay ewe with twins. Photo from the St Kilda Soay Sheep Project, which monitors and studies the wild population on the island.

Soay horned ewe with her lamb. Soay Sheep Breeders Cooperative

The tan-faced mountain breeds, still surviving in many variations, descend from medieval stock of marsh and hill sheep. Intelligent and very hardy, the ewes have a keen sense of direction and remember migratory trails from season to season. The mountain breeds generally have a coarse, hairy outer-coat over a fine woolly under-coat. The wool is loosely packed, even stringy in appearance, allowing the sheep to dry out quickly after a sudden downpour or washing.

Dalesbred, a mountain breed, showing the luxuriously long and dense coat. www.nationalsheep.org.uk

Dalesbred ram, with splendid horns. Dalesbred Sheep Breeders Association

The Danes brought over native multi-horned sheep during the Viking invasion, some with as many as six horns. There may have been some breeds native to the British Isles which also sported horns in multiples, as noted by Robert Trow-Smith in A History of British Livestock Husbandry, 1700-1900:

…four or six-horned sheep is also to be found in the Isle of Man under the name ‘loaghton’. It, and indeed all the other native Scottish sheep types, is commonly given a Scandinavian origin and said to have been brought in by the Vikings. That may be so; but it should be noted that sculls and horn-cores of four-horned sheep have been found in undated deposits at Jarlshof (an ancient site in Shetland, Scotland), where the long succession of sites ranges from Bronze Age to late mediaeval dates, and the arrival of this sheep could have equally well have occurred earlier – or later – than the Viking settlement.

Their descendants are still bred for fleece and flesh in Britain. They found their way into ornamental sheep parks for the gentry in the seventeenth century.

A Manx Loaghton sheep, with characteristic four horns. Manx Loaghton Sheep Breeders Group

Interested in sheep and sheep lore? Shire Album #157 British Sheep Breeds by Elizabeth Henson is a marvellous little book. And Dorothy Hartley’s Lost Country Life, Pantheon Books, is an exhilarating and inexhaustible mine of information on medieval trades and daily life.

wonderfull source of knowledge