Scandinavian Archetypes in North American Imaginations:

From Beowulf to Alicia Vikander

A talk presented at the Ingmar Bergman Estate, Fårö, 27 May 2016

I am American of English descent, and write novels set in 9th century England and in Gotland. You will hear me use the term “Viking” and “Viking Revival” in this talk, but I want to note that historically this term was virtually unknown in the English language.

The first Oxford English Dictionary reference of “Viking” only dates from 1807. And in fact I never use it in my novels, set in the 9th c, as my characters do not use it. The Anglo-Saxons in England, suffering from Viking attacks, never used that word; they did not know it, and it was a rarely used term in Old Norse. My “Vikings” were simply “Danes”, or “the heathen horde”.

Having established this nomenclature: let me take you to New England, specifically Massachusetts. What we are seeing here is found on Boston’s most elegant residential street, Commonwealth Avenue. This statue of Leif Erikson is by Boston sculptor Anne Whitney, 1887.

Boston Leif Erickson Statue

Detail Boston Leif Erikson Statue

My talk is entitled Scandinavian Archetypes in North American Imaginations and I can’t actually begin with this statue, because the fascination goes back further, much further if you count the greatest archetype of all in the minds of English-speakers, and that would be Beowulf.

Beowulf Manuscript, first page

Beowulf is the great hero of an epic poem dating probably from the 8th century, written down in Old English, and having nothing to do with England. It celebrates, in over 3,000 lines of stirring poetry, the earliest Scandinavians to have impressed the English mind. It’s the foundation of all later English poetry and a great cultural touchstone, because of the intense identification the Anglo-Saxons had with it; they saw their earlier selves reflected in the greatness documented in the poem. And for good reason, because the Angles and the Saxons and the Jutes came to Britain beginning in the year 450, from the very same areas to the East that the later Danes would launch their devastating attacks from.

Beowulf, by the way, swam past Gotland when he swam to Finland – one of his many extraordinary feats. He was a Geat, a very great warrior with super-human powers, who aided the Danes, and later became a wise and just king, who died after battling a dragon to the death.

Beowulf was first translated into Modern English in 1805, followed by other translations, into Latin, for instance. These began appearing in the scholarly collections of educated Americans and Canadians. So Beowulf came to North America before 1850; there was a copy at the Boston Athenaeum by 1848.

We need to keep Beowulf in mind, because he encapsulates very neatly many of the virtues that have always been dear to the frontier mentality of the settlement of North America, that is, a kind of heroic individualism tempered with democratic and law-giving proclivities.

It’s also a good model for us, because of the mixture of fact and fantasy in Beowulf. The poem mentions real places, and some real people, combined with idealized aspiration. And that’s one of the things we will be looking at, this combination – juxtaposition – of the Real and the Fake in our subject.

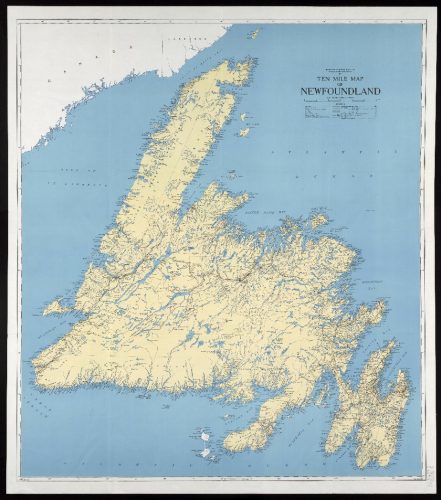

This is real:

Map of Newfoundland

This is the province of Newfoundland on the East Coast of Canada. The settlement of L’Anse aux Meadows at the very northern tip of Newfoundland is accepted now as being the celebrated land that Leif Erikson sailed for from Greenland, and which he named “Vinland.”

Two Norwegians, the explorer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, excavated the remains of a Norse village at L’Anse aux Meadows between 1961 and 1968. This is Anne Ingstad on the site.

Anne Stine Moe Ingstad (1918-1997)

The large grass-covered mounds there had been thought to have been an “old Indian camp”, but they were struck by the similarities to remains on Greenland. What they found were eight complete house sites and parts of a ninth. Here is a reconstructed house at L’Anse aux Meadows.

l’Aanse aux Meadows

The name “Vinland” is significant, as it is mentioned in the Icelandic Sagas – The Saga of The Greenlanders and The Saga of Erik the Red – and people always assumed that the land Leif had landed at had grapes. In the 19th century it was thought that the furthest North one could go around the year 1000 and successfully grow grapes was Massachusetts. But that was wrong; there was the “little ice age” beginning about 1300 that made things far colder than they were when Leif and his followers were looking for new land to settle on. And in fact the Ingstads felt that the name “Vinland” was a corruption, and actually meant something closer to “A meadow land near a peninsula”.

As we all know, the settlement was not a successful one. The climate was quite harsh in Winter and the native population were far from welcoming. The band of pioneers returned home; Leif himself died in Greenland about 1020.

Just recently American archaeologist Sarah Parcek, working with satellite images, identified another potential Norse settlement of the same era 300 miles southwest of L’Anse aux Meadows, at Point Rosee, Newfoundland, which remains to be thoroughly excavated and dated. But the remains of turf foundation walls and a piece of iron slag suggests Norse technology.

This is what we know today, as close to “fact” as modern archaeology and all its technology can get us, at this point. But back in the late 19th century, the figure of Leif Erikson became very important in North America, particularly the United Sates.

Boston Leif Erickson Statue

The idea of placing a statue of Leif Erikson in Boston, of all places, dates to 1877. It was championed by Ole Bull, a Norwegian violinist living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who was enthusiastically joined by the great and revered Boston poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. They got up a committee and raised funds, influenced by the idea of the Danish scholar Carl Christian Rafn, that the Vinland mentioned in the Sagas was in fact in New England.

A chemistry professor at Harvard, Eben Horsford, who had made an immense fortune in discovering and marketing double-acting baking powder, joined this effort. Prof. Horsford was influenced by early maps of North America, those from the early 16th c, and legends about a land called “Norumbega” by an English sailor, of fabulous wealth and gold and gemstones in an area that looked, to his reading of the old maps, to be none other than Boston Harbor. This led to the “Norumbega craze”, 19th c Bostonians wanting Boston/Cambridge to be the lost and fabled land Leif discovered.

Prof. Horsford, who had more time and money than was good for him, became convinced that Vinland and Norumbega were one and the same, and that the Vinland Leif Erickson landed on was in fact Boston and Cambridge. Again, remember the grapes – it was agreed that Massachusetts was the furthest North that good wine grapes could be grown in the year 1000.

Horsford carried out some perfunctory excavations and claimed that Leif and his followers had created a metropolis of no less than 10,000 inhabitants that lasted 350 years, along the banks of the Charles River, which is the river that divides Boston from Cambridge. He decided that the name “Norumbega” was a corruption of “Norway”, so that was convenient. He didn’t seem to care that a settlement of 10,000 people would leave a huge amount of artifacts behind, and wasn’t particularly troubled by the fact that he couldn’t find any. He just drove his carriage up alongside the Charles River to the suburban town of Newton and noted some rocky ground and called it the site of Leif Erickson’s house. He built a tower there, called Norumbega Tower, to commemorate his deductive brilliance. Here is the tower:

Norumbega Tower

Similarly, a handsome bridge was built over the Charles River in honour of Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, the famous poet who supported the idea of the Leif Erickson Statue. This is the base of the bridge, and as you can see, it has the prows of Viking ships on it, to mark Leif’s progress up the Charles River.

Longfellow Bridge, Boston – Cambridge

Longfellow Bridge Piers with Ship

This sense that Leif Erikson had landed and settled in greater Boston was pursued with a sense of urgency, even a sense of moral imperative. Why?

To use against this man, Christopher Columbus.

Christopher Columbus

Everyone knew that in 1492 Columbus “discovered” America, accidentally, of course, on his way to try to find a route to India. Columbus was Italian, from Genoa, and a Catholic, and his voyages were financed by the very Catholic monarchs of Spain, Isabel and Ferdinand.

Boston was a decidedly Protestant city, founded in 1630 by English religious dissenters, and up until the last quarter of the 19th century, strictly ruled and governed by the Protestant descendants of the founding fathers. But this was beginning to change. There had been a massive influx of Irish immigrants to Boston during the years of the potato famine in Ireland, and beginning in 1845 40,000 Irish came to Boston a year, for the next five years. Most of them were Catholic.

In 1884 the first Irish Catholic, Hugh O’Brien, was elected Mayor of Boston. This was the beginning of a big power shift in Boston politics and a reflection of the social upheaval going on. Suddenly the Catholics were ascendance in Boston leadership.

And emigration from Catholic Italy was picking up too, so that by 1910 the Italian population of Boston was about 30,000.

1892 was the 400th Anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America, and there was a big movement on amongst Catholics in the United Sates to name him a Saint. This was threatening to the non-Catholic power base; there was a great deal of anti-Catholic sentiment then, both aimed at Italian Catholics and Irish Catholics.

So Leif Erikson became a kind of alternate answer to this fear. Some people in Boston, and throughout other parts of the United Sates, wanted to desperately believe that America really had been discovered and even settled by a Norwegian “Viking”, and not by an Italian Catholic like Columbus.

It’s quite embarrassing if you look back at it now, but fear and bigotry makes people do embarrassing things.

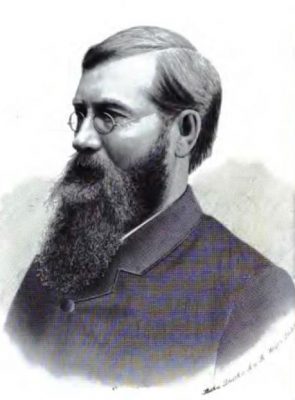

It wasn’t just in Boston, either. Rasmus Bjørn Anderson, born in Wisconsin in 1846 to Norwegian parents was an American author, professor, and diplomat. He wrote the book America Not Discovered by Columbus in 1874, and was the originator of Leif Erickson Day.

Rasmus B. Anderson

Leif Erikson Day is October 9th (suspiciously close to Columbus Day, October 12th). It is still a state holiday in Wisconsin, and was established there in 1930 and in Minnesota in 1931. October 9th was chosen because the ship Restauration coming from Stavanger, Norway, arrived in New York Harbor on October 9, 1825, at the start of the first organized immigration from Norway to the United States.

Here’s a postage stamp commemorating the event 100 years later.

Viking Ship Postage Stamp

The fascination was not confined to the East Coast, or to the late 19th century, either: There is a Leif Erikson statue in Seattle, unveiled as recently as 1962 for the World’s Fair held there.

Seattle Leif Erikson Statue

This is not to say there wasn’t real underpinnings to the admiration and fascination with all things Nordic that folks in North America embraced. There was in reality a long but interrupted Scandinavian history in America, beginning with the colony of New Sweden, founded by the Swedish West India Company on the Delaware River in 1638. At its largest, it had about 600 Swedish and Finnish settlers. It was short-lived, only 17 years, as it was overtaken by the Dutch colony of New Netherlands in 1655; but Swedish was still spoken by the descendants until the end of the 18th century. And there is still a large Swedish American Museum in Philadelphia, and other landmarks like Fort Christina State Park in Delaware.

Real Scandinavian immigration began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One-point-three million Swedes came to the United States. They came as families because of the availability of high quality, inexpensive farm land in the Great Plains, which is the Upper Mid-West, the states of Illinois all the way West to Montana. After steam ships became common, about 1870, transatlantic fares, even for people of moderate means, became affordable, and by 1880 American railroad companies actually had agents in Sweden who arranged package fares, shipping out the entire family, farm implements, furniture, everything the family would need, to their new farmland. There were financing plans so that families could pay this off over a number of years, and it made a very attractive package offer. Young Swedish men came as well, lured by the high paying factory jobs in big cities like Chicago and Minneapolis. These are areas which still have large numbers of people of Swedish descent.

The United States Census of 1890 recorded a Swedish-American population of almost 800,000 people, so much of that 1.3 million who immigrated were there by 1890. Smaller but still significant numbers of Swedes left for Canada during the same time, most settling in the milder Western portion of that vast nation.

Similarly, Norway saw even a greater proportion of its citizens leave for America – almost one million people. Only Ireland contributed more of its population to the US than Norway did.

So we had, at the very same time, not only a real influx of people from Sweden and Norway coming to the US and Canada, but a desire in the US amongst some leaders for the nation to have really been discovered and settled by none other than Leif Erikson. All this led to two things: lots of fake discoveries, and the Viking Revival.

We’ve already heard about the spurious claims that the Boston area was Vinland. In the next few decades all sorts of “Viking rune stones” would be discovered in Minnesota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and others; “Viking weapons” unearthed, and various “Viking towers” identified.

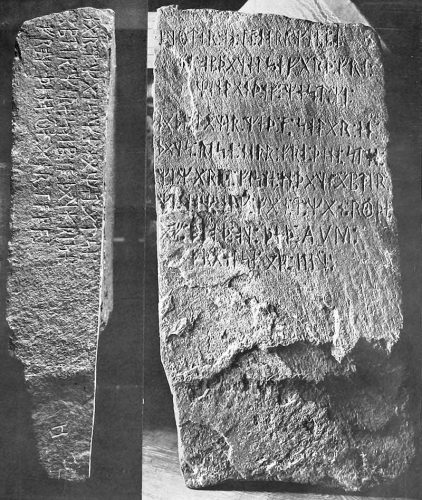

The Kensington Runestone is a 202 pound (92 kg) rock inscribed with runes on its face and side. A Swedish immigrant, Olof Ohman, claimed to have discovered it in 1898 in Douglas County, Minnesota.

Kensington runestone from 1910

The text translates to:

“Eight Geats and twenty-two Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vinland to the west. We had camp by two skerries one day’s journey north from this stone. We were [out] to fish one day. After we came home [we] found ten men red of blood and dead. AVM (Ave Virgen Maria) save [us] from evil. [We] have ten men by the sea to look after our ships, fourteen days’ travel from this island. [In the] year 1362.”

It was dismissed as a hoax even then, based on linguistic evidence. But again, Leif Ericson comes into play, and this idea that he had somehow settled America.

Five years earlier Norway had sent a replica of the Gokstad ship, called Viking, to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. This appearance made quite an impression on people, and was of course a source of pride to Norwegian Americans. This is the Viking at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.

Viking, replica of the Gokstad Viking ship, at the Chicago World Fair 1893

This ship miraculously still exists and is undergoing complete restoration in Chicago.

So called rune stones were even found in states like Oklahoma, all probably created by 19th c Swedish and Norwegian settlers. Sometimes rocks were found with actual Native American markings on them, and people were eager to ascribe these as “Viking rune stones” as well, even if none of the figures were actually runes.

In Canada a cache of authentic Viking age weapons and metal work was buried and then dug up near Beardmore, Ontario, and then called the Beardmore Relics. It was a very convincing hoax, as the sword blade and axe head were truly Viking era weapons, and were used as “proof” of Viking settlement in Ontario. In the 1930’s the distinguished Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto bought the weapons and displayed them; it wasn’t until the late 1950’s that the son of the man who had found them admitted his father had planted the relics.

What was all this about? In the United Sates there was the goal of discrediting Columbus as the discoverer of America. And in both the US and Canada there were large numbers of new immigrants, proud of their Scandinavian heritage, and wishing to express this pride. Back at home there was a growing sense of modern Nationalism, as Scandinavian nations which had been associated with others – Norway for instance becoming an independent nation in 1905, having been in union with Denmark and then Sweden – began seeking unique and distinctive identities, and the Viking Revival correlated with this rise of national pride.

And: True Viking era artifacts begun being discovered: the 22 m long Tune ship, used for a burial c 900, was found in Østfold, Norway in 1867.

Tune Ship

Discoveries such as the Tune ship helped fuel the so-called Viking Revival. As romanticized as some of the Viking Revival imagery was, it was rooted in a deep desire for heroic foundation stories, and an outlet for the pride and connection people felt in the old homeland.

19th c Winged Viking

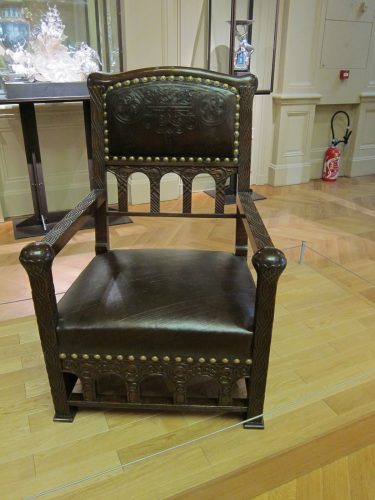

The Viking Revival was even reflected in furniture design: here is a Tiffany Studio Viking Revival c 1900 chair, made in New York.

Tiffany Viking Revival Chair

Tiffany Viking Revival Chair Detail

What other Scandinavian archetypes have had an impact on North American imaginations? Leaving aside the many contributions in diplomacy, such as the great Dag Hammarskjöld and Olaf Palme – two martyrs to justice – or someone like Alfred Nobel in science and technology, it is typically in the realms of sport and entertainment that Scandinavian influence is most felt, certainly in the US. Here’s a quick series of images that represent facets of that archetype:

Jenny Lind

Celebrated soprano Johanna Maria Lind, born in 1820 and better known as Jenny Lind, was hugely successful and popular in America, earning over $350, 000 in tour fees.

Garbo in “Inspiration”

The magnificent Greta Garbo, who has justly been called the first “modern woman”, both assertive and feminine.

Ingrid Bergman in “A Woman’s Face”

The beloved actress Ingrid Bergman.

Ingmar Bergman laughing

“The Dour Swede” was a reputation fostered by the films of Ingmar Bergman. Or as Wikipedia so succinctly puts it, “His work often dealt with death, illness, faith, betrayal, bleakness and insanity.” I like this image because he is laughing.

We must include at least one photo of the automobile so continually popular in the US, which embodies stylishness and safety, both: Volvo. This is a Volvo C-70.

Volvo C70 Convertable

But to return to the world of sport or entertainment, a few talents which made an indelible impression in the US:

Britt Ekland

Actress Britt Ekland.

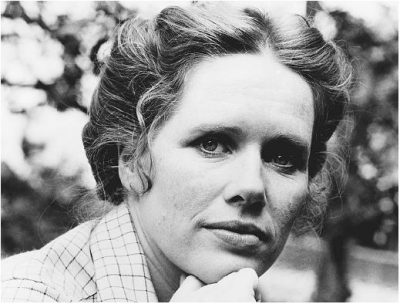

Liv Ullman

Actress and Ingmar Bergman leading lady Liv Ullman.

Alicia Vikander

Actress Alicia Vikander receiving her Oscar in 2015.

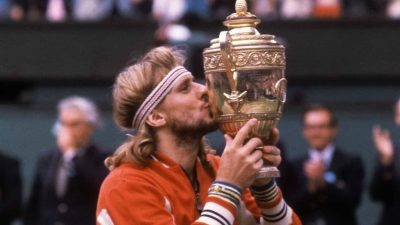

Bjorn Borg

Tennis great Bjorn Borg.

ABBA

Pop superstars Abba.

and of course the rollicking Vikings of TV, to bring us full circle.

Vikings TV Show

We’ve looked at fact, and at fantasy in the ways that Scandinavian Archetypes have acted on North American Imaginations. The connections are deep, long-lasting, and continually developing. Thank you.

The author acknowledges the work of Gloria Greis, Executive Director, Needham Historical Society, and her entertaining and illuminating essay Vikings on the Charles for the discussion of Leif Erikson and Eben Horsford.

Recent Comments