The Buildings of the Anglo-Saxons,

450 CE to 1066

Wondrously ornate is the stone of this wall, shattered by fate; the precincts of the city have crumbled and the work of giants is rotting away. There are tumbled roofs, towers in ruins, high towers rime-frosted, rime on the limey mortar, storm-shielding tiling scarred, scored and collapsed, undermined by age…..There were bright city buildings, many bathhouses, a wealth of lofty gables, much clamour of the multitude, many a mead-hall filled with human revelry – until mighty Fate changed that. from The Ruin from the Exeter Book (c 975 CE), translated from Old English by S.A.J. Bradley

The poet of The Ruin tells of looking with wonderment on the remains of a fallen city built with such craft that it seems “the work of giants”. This may the Roman city of Aquae Sulis – Bath, seen through Anglo-Saxon eyes. With the Roman settlement of Britain came their typically inventive and ingenious works of architecture and engineering – precisely surveyed and constructed roads; opulent stone villas – some with sixty rooms – featuring enclosed gardens, furnaces and chimneys; thriving trading cities with sewers and public baths; manufactories of ceramic, glass and metal work of every kind. Such trappings of Mediterranean civilization required not only initial effort but ongoing maintenance. Once the legions withdrew the unprotected cities fell prey to lawlessness, neglect, and finally abandonment.

Mercenary soldiers from the marshy shores of modern northern Germany and Denmark, originally imported to help police the Roman settlements, turned on their employers and sought land for themselves. This began a flood of immigration of tribes who would be known as the Angles, Saxons, and to a lesser extent, Jutes. Their native building forms were wooden buildings in simple farmsteads. Fishing, hunting, and subsistence grain and vegetable farming provided for their wants. They turned their back on the Roman cities and the foreign way of life suggested and necessitated by such buildings and communities. Instead they exulted at the wealth of woodland and fertile farmland in their new home. It was the abundant forests of what would become known as Angle-land – Engle-land – England which set the tone for much of the building these new settlers would undertake.

English woodlands yielded not only the raw material to saw long and broad timbers for the erection of walls and cross beams but a wide variety of specialty building products. Coppiced trees will sprout straight slender shafts within weeks of cutting; such growth is ideal for lightweight building poles, fencing – and the shafts of spears. No less an Anglo-Saxon personage than King Ælfred (ruled 871-899) exhorts his readers to “to wend his way to the same road where I cut the props (and) load his waggons with fair rods that he may weave a fine wall, and set up many a goodly house.” Although the King was speaking metaphorically about the forest of philosophical wisdom, the diverse practical uses of the English woodland are made clear. In fact wood virtually defines early English building.

“Timbrian” is the Old English verb for “to build” and the very noun “timber” synonymous with “a building”. The act of building itself was “getimber” – timbering. “Timbrend” is “a builder”. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle notes that Ælfred’s able and politically savvy daughter Æthelflaed, known as the Lady of the Mercians “timbered the burh” when she built a fortified base near the Welsh border in 915.

It is in fact the great, vanished timber halls which most readily come to mind as the products of early English architectural efforts, and native forests provided ample building material. But we must not assume that all early Anglo-Saxon buildings were wood framed; there were many of stone. In certain instances stone was even reused from abandoned Roman structures; the tiny but rugged church of St Johns at Escomb (7th/8th century) is built of stone blocks pilfered from the Roman fort at Binchester. Brixworth Church in its earliest incarnation (c 680) was also built with Roman bricks from nearby ruins. Up in York the massive Roman headquarters and surrounding wall was used until the headquarters was finally pulled down about 800 during the expansion of the town. At that time the headquarters still was roofed, and the interior had been divided for new uses; one former office has been identified as being reused as a metal working shop. Reuse of Roman building materials went on a long time. Even the Normans were using Roman bricks from the Roman town of Verulamium to help augment the local flint in the building of the cathedral of St Albans in Hertfordshire.

Huts and Timber Halls

The majority of Anglo-Saxon buildings were wood frame residential structures and outbuildings. Buildings could be one, one and half, or two stories high. Wood framed walls were constructed in two ways: either from split, planed timbers cut all to the same height and set upright on a wood or stone sill, or wood frame with materials such as wattle and daub or nogging used in the interstices between large timber uprights. The large timber uprights could be placed into individually dug post holes, or into a continuous trench. Iron nails were widely used to fasten timbers, but as so little actual wood work has survived it is impossible to guess at the type of joinery house builders used, although there is no reason not to imagine that it was often at a high level. Mortise and tenon and dovetail joints were likely employed amongst many other fastening techniques, some of which were adaptations for the craft of shipbuilding. Axes, adzes, wood-splitting wedges, saws, chisels, spokeshaves, gouges and spoon-bits have been found to give us an idea of the range of tools available to building wrights. Lathes were also known, so that turned ornament or features may have been employed in the interiors.

In areas less blessed with timber, walls of cut stacked turf and cob have also been found. A broad variety of organic materials were impressed into service as building materials. For example, moss and ferns were sometimes used as insulation to stop up gaps around wattle work and help seal out the cold and damp.

Buildings were square, rectangular, and round in plan. A central fire pit provided warmth and light, with smoke making its imperfect escape through a hole in the (typically) thatched roof above. The simplest and most prevalent floors were of pounded earth, but wooden and stone floors were used as well. Evidence of wattle mats have been found in the remains of wattle and daub houses in 9th and 10th century Viking Dublin, and such matting was very likely employed in Anglo-Saxon settlements as well. Particularly earlier in the Anglo-Saxon period some buildings had excavated, or sunken floors. When planked over these were used as cellars, but in certain instances the actual floor of the building was lower than ground level.

Many of the smallest domiciles were windowless with light only being admitted when the wooden door was open. Such modest dwellings would contain the simplest of furniture, all made of wood – a bench or two, a rude table, some stools.

The variety of buildings in early settlements such as shown at the reconstructions at West Stow in Suffolk (450 CE-750) indicate that related families lived in smaller houses and socialized together in a larger hall. At West Stow there may have been four or five extended families and their slaves housed in a variety of timber and wattle and daub buildings roofed with thatch.

The timber halls or “great halls” of wealthy thegns, reeves, ealdormen, lords, and kings occupied a unique place in early English society. As modern scholar Stephen Pollington puts it:

These halls served as the focal points of the communities they served – all commercial business was witnessed there, all justice was enacted there, all judgments were spoken there, all contracts were made and dissolved there, all praiseworthy deeds begun and ended there.The Mead-Hall: Feasting in Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon Books 2003

Fyrkat. A long house under construction. The entire ring fort and neighbouring village will be recreated in an ambitious living history scheme.

Fyrkat. Interior of long house, showing timber framing and half-thatched roof.

Fyrkat. A wattle wall under construction. Staves are being woven between the larger uprights – a good example of King Ælfred’s injunction to “weave a fine wall”. Photos by Jonathan Gilman

Fyrkat. A mid-20th century reconstruction of a Danish great hall and long houses in Hobro, Denmark. Fyrkat was the site of a fortified ring fort, one of four created by Harald Bluetooth in 980, and was made up of 16 large buildings, including barracks for warriors, storehouses, and workshops. It gives a good idea of contemporaneous English construction.

Such buildings were not only of necessity larger than the dwellings of the humble but of a specific shape – long and narrow. Some great halls were built in the style now referred to as “bow-sided” – that is broadest in the centre of the building and tapering slightly at either end.

Great halls typically had two doors, one at either end of the hall, and one door might open into a shallow anteroom. There might be a window or two, usually unglazed but with wood shutters for defense and protection from weather. The central firepit remained, but along the exterior walls recesses or alcoves were built which served as places to sit or do hand work during the day and to sleep at night. Along one of the long walls would be a raised step or dais at which sat the chairs of the lord and lady. On either side of these “high seats” ran benches for their men – the “mead benches” sung of in so much Anglo-Saxon poetry. More experienced and valued warriors sat closest to the lord and lady, while younger men sat on the other side of the fire pit along the opposite long wall. Sometimes a separate room was located at the end of the hall, which may have served as a private chamber for the lord or a strong-room for the storage of the most important treasure of the household – weapons and the plate that the family and esteemed guests ate and drank from. Stone and clay cressets filled with oil cast light at night, as did torches soaked in oil. Wooden furniture included the aforementioned chairs (for high-status guests and their hosts), benches, and trestle tables which could be easily knocked down and stored when meal time was over.

Of interior decoration for wooden structures we must look to the remains of stone buildings and to poetic descriptions.

Lime washing on wood gave a welcome brightness to dark interiors and could serve as a ground for coloured mineral pigments. In the tradition of the richly decorated surfaces beloved of the Anglo-Saxons, in the halls of the wealthy the large structural timbers exposed to view may have been highly ornamented with carving and paint. The Beowulf poet describes Heorot, the fabled hall of Hrothgar which Beowulf visits as:

“…a timbered hall…furnished and gold-fair – it was the most renowned among dwellers on earth of buildings beneath the sky – in which the great man dwelt; its brightness shone out over many lands…lines 1.306-11, translated from the Old English by Stephen Pollington

At Goltho in Lincolnshire the fortified burh of a wealthy lord has been excavated. It comprised a bow-sided timber hall nearly 25 m (82 feet) long and nearly 10 m wide (32.8 feet); a smaller kitchen building set well away from the hall for fire protection; a long narrow weaving shed about 20 m long where the women of the burh would have stood at their looms for the daily labour of wool weaving; and a separate bower building.

Private defended burhs of wealthy thegns, ealdorman, and nobles could include both large timber halls and smaller stone buildings. The remains of a Saxon masonry building of 2.4 m (8 feet) tall stone walls have been excavated at Eynsford castle, Kent. A wood framed roof may have rested upon the walls, or they may have carried another wood-framed story above. This building had an excavated floor some 1.5 m (5 feet) below the ground, and was surrounded by a ditch 5 m (16 feet) wide and 3 m (10 feet) deep. Heavily fortified as it was it may have housed a powerful lord. On Lower Brook Street in Winchester was found the remains of a square stone building of at least two stories dating from about 800. It is part of a high status, secular, residential homestead.

At Sulgrave, Northamptonshire excavations have revealed the presence of a large 10th c timber hall, another lordly residence. Like many great halls it was constructed of closely set vertical timbers. At Sulgrave these sat upon a laid, mortar-less stone foundation. At one end of the great hall was a partition which led to a smaller room – perhaps a store room. A smaller detached timber building, which may have been a kitchen, was built outside. Another building on the site had stone walls more than 2 m (6 1/2′) high – possibly a strong room or tower.

Roofs were structured of timber, typically thatched with the reeds found along so many English waterways, but wood shakes, lead sheets, and tin roofs were also known. The celebrated churchman and intellectual Alcuin (d. 804) gave tin for a roof in Eoforwic in 801. (Eoforwic rose to eccessiastcial fame under Alcuin’s teacher Albert, who became Archbishop there and held that post from 767 to 778. Albert created a new church in Eoforwic, St Sophia, with a scriptoria renowned for the fineness of its manuscripts. Alcuin described the church thusly:

“A lofty building, raised on solid piers

Supporting round arches, and within

Fine panelling and windows made it

bright, A lovely sight, with gleaming

cloisters round And many upper rooms

beneath the roofs And thirty altars

variously decked.”

All traces of church and scriptoria were obliterated during the violent Viking capture and takeover in 876. The “high walled and towered” city described by Alcuin was destroyed. The Danes who settled there renamed the city Jorvik – York. They rebuilt the city along Danish lines and it became a thriving trade centre.)

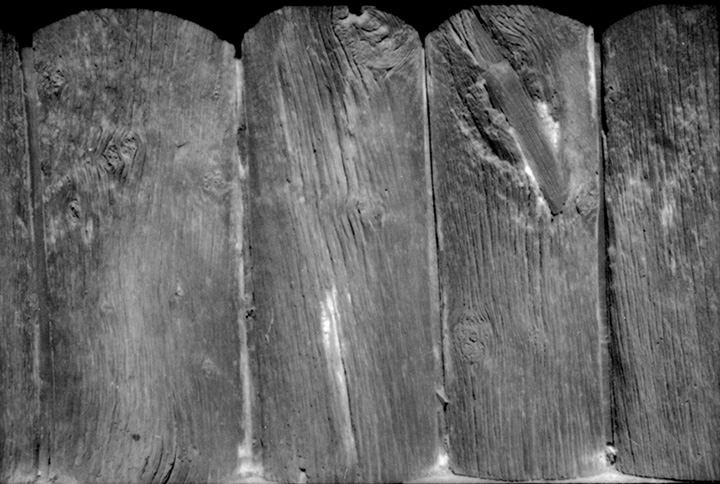

One wooden church which has survived is St Andrews, Greensted, Essex, the timbers of which have been recently dated to the early 11th century. The ancient walls are an unique survival of a type of wood construction – the upright oak timbers have been split in half length wise so that the rounded dimension of each half still shows.

St Andrews, Greensted, Essex. View of rear of church.

St Andrews, Greensted, Essex. The body of St Edmund lay here overnight in 1013 on its way from London, whence it was removed for fear of the Danes, to its final resting place – fittingly to be known as Bury St Edmunds. Edmund was King of East Anglia and was defeated in battle by the Dane Halfdan in 869 or 870 and executed. He soon became a subject of veneration. This tiny church is the sole surviving timber church of the Anglo-Saxon era (although other churches have some Saxon timbers). The brick sill underneath the timber was a Victorian addition.

St Andrews, Greensted, Essex. Close up view of ancient timber wall. Photos by Jonathan Gilman

We know of other types of early English timber construction. A large tiered wooden grandstand reminiscent of theatre seating was built at Yeavering in Northumbria, which may have provided seating for those assembled to hear the preaching of Christian priests, particularly that of Bishop Paulinus. It was part of a large royal residence of Edwin of Northumbria, who though initially heathen, wed the Christian daughter of King Ælthelbert of Kent in 625, thus bringing Paulinus in her train.

Stone Construction

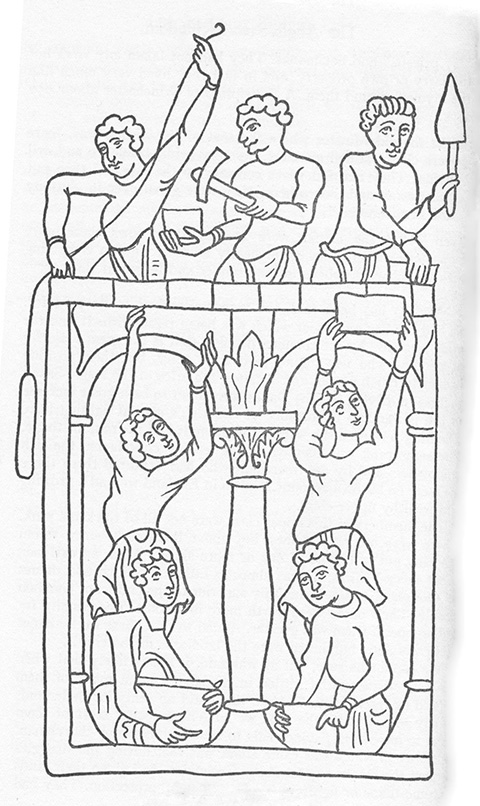

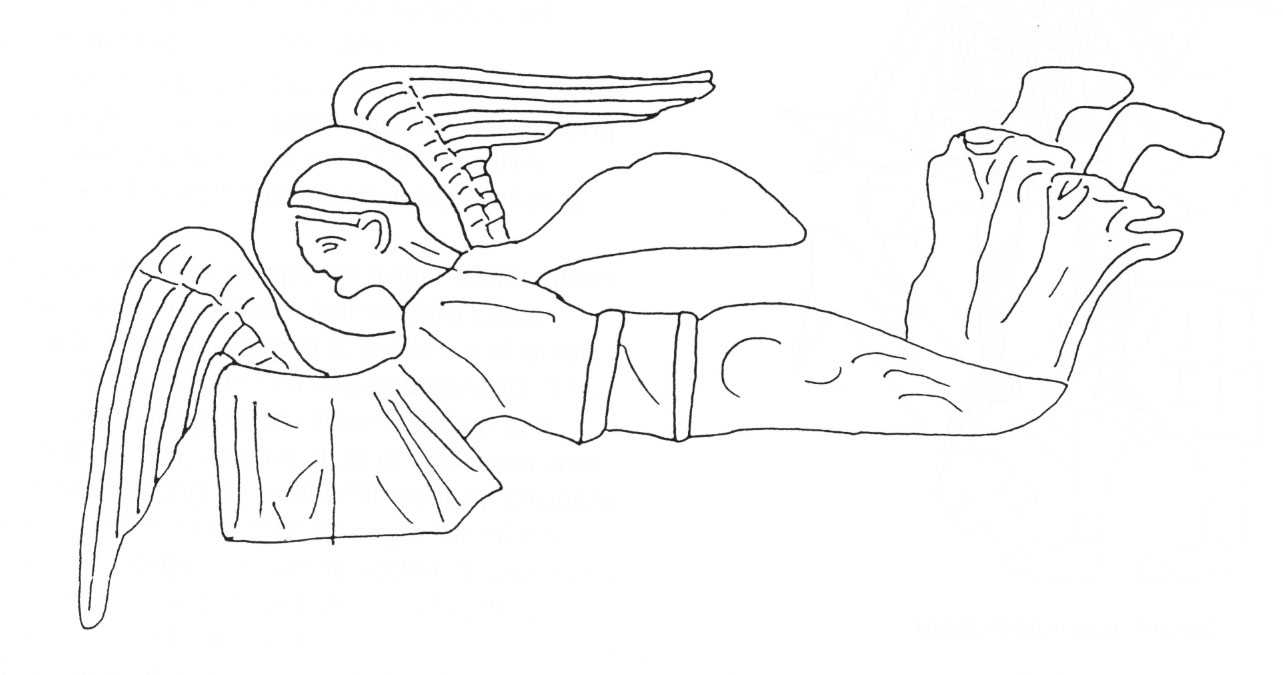

Below, masons of the 11th century at work. One, perhaps the master-mason, lowers a plumb line to check the squareness of the masons’ stone laying. The essential materials and tools of the mason’s craft remain unchanged for more than two thousand years – hewn stone, trowels to spread mortar, plumb line to ascertain square and level construction.

It is likely true that many early churches were of timber, but it is clear from both archeological and textual evidence that many were of stone. Some Anglo-Saxon stone churches were in fact adaptations of churches originally built by Roman Christians, for there were Christians in Britain by the second century CE. (In some cases these basilicas had been heathen temples before Christianity became widely adopted amongst the Romano-British population) The Venerable Bede (c 673 – 735) wrote that the original cathedral at Canterbury was of basilica form with an apse (half round wall) at each end. It had been used as a Christian Church under Roman rule, and it is thus fitting that it is still considered the mother church of the Anglican Communion. This early building was repaired by St Augustine in 602 (at which time it had two towers), enlarged by St Cuthbert about 750, and again by Bishop Odo in 940. All of the ancillary buildings – the cloisters, refectory, workshops, and so on – were likely of timber, but the sanctuary itself was stone. (In 1067 the cathedral was utterly destroyed by a devastating fire, and the Normans built anew.)

It is likely true that many early churches were of timber, but it is clear from both archeological and textual evidence that many were of stone. Some Anglo-Saxon stone churches were in fact adaptations of churches originally built by Roman Christians, for there were Christians in Britain by the second century CE. (In some cases these basilicas had been heathen temples before Christianity became widely adopted amongst the Romano-British population) The Venerable Bede (c 673 – 735) wrote that the original cathedral at Canterbury was of basilica form with an apse (half round wall) at each end. It had been used as a Christian Church under Roman rule, and it is thus fitting that it is still considered the mother church of the Anglican Communion. This early building was repaired by St Augustine in 602 (at which time it had two towers), enlarged by St Cuthbert about 750, and again by Bishop Odo in 940. All of the ancillary buildings – the cloisters, refectory, workshops, and so on – were likely of timber, but the sanctuary itself was stone. (In 1067 the cathedral was utterly destroyed by a devastating fire, and the Normans built anew.)

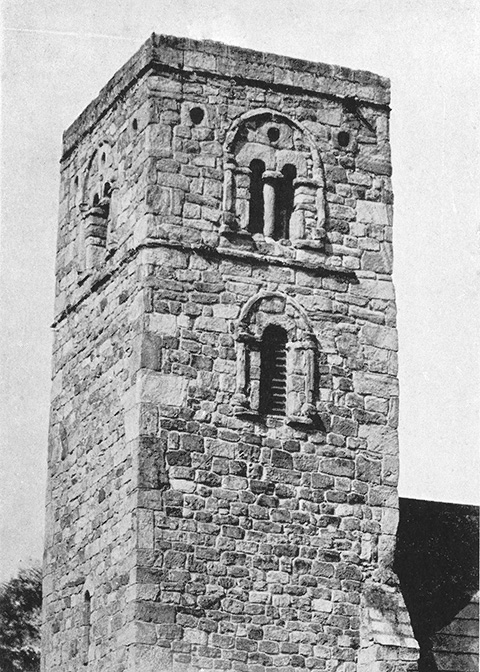

In Northumbria the church of St Andrew in Bywell retains its Anglo-Saxon tower of multi-hued sandstone. It may date from as far back as 850, and has walls 5 m (16 feet) thick.

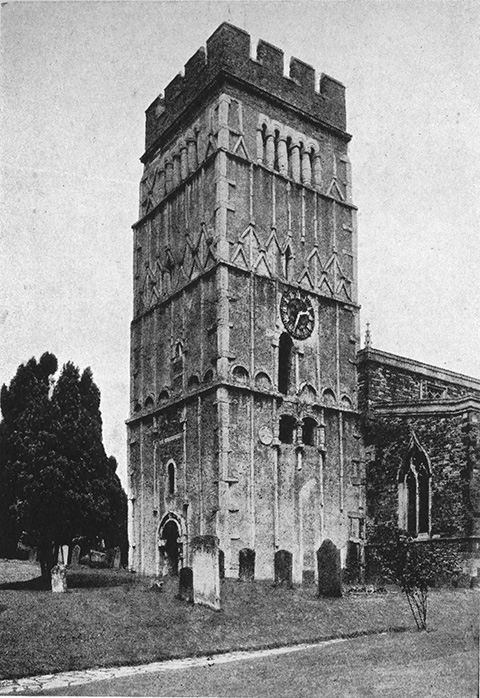

The beautiful tower of All Saints Church in Earls Barton Northamptonshire dates to 970 and holds especially interest in that the stonework is imitative of timber. The battlements at top are of a later medieval date. Earls Barton also features a substantial earthwork, and it is possible that it was the site of a Saxon burh.

St Andrew in Bywell

Photo by F. H. Crossley

St Laurence Church, Bradford-on-Avon

Photo by Michael Holford

All Saints Church, Earls Barton

Photo by Brian Clayton

Church floor plans varied widely. Small porches or chapels were built onto simple rectangular churches, such as the small and jewel-like Bradford-on-Avon in Wiltshire. The lower part of this church may date from as early as 705, and the arcades from the end of the 10th century.

The Old Minster in Winchester, precursor of the modern Cathedral there, had when built in the 7th century a rectangular nave, square chancel and two small side chapels. Sometimes these buildings became incorporated into later larger churches which still stand: The present day parish church at Jarrow has as its chancel such an early church.

Only a few Saxon churches featured the classical “basilica” plan with apse (half round wall at one or either end). The impressive All Saints Church at Brixworth, Northamptonshire, parts of which date to the 7th century, is one which demonstrates this feature.

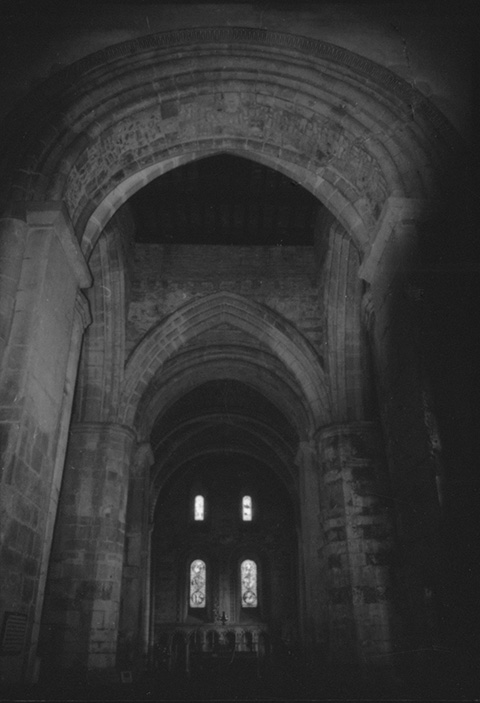

All Saints Church, Brixworth

All Saints Church, Brixworth. Interior looking toward apse. The (modern) plaster on the interior would have been richly overpainted with images of saints, parables, object lessons and Bible scenes. Pews are a convenience unknown to our hardier Anglo-Saxon forbears; worshippers stood throughout the service. Photo by Jonathan Gilman

The large and important monasteries at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow and founded in 674 and 681 respectively by Benedict Biscop, were distinguished by the ambitiousness of their building scheme. Benedict had travelled to Gaul and was unimpressed with the wooden churches of Northumbria. He imported stonemasons and glassmakers from Gaul and built a monastery complex at Jarrow of masonry buildings with concrete floors, coloured glass windows, and tinted plaster walls. The remains of his stone basilica dedicated in 685 survive incorporated as the chancel of the church of St Paul, and the dated dedicatory stone can still be seen. At the monastery at Monkwearmouth the still-extant western porch issued from Benedict’s hands. It was originally two stories high, over 10 m tall (33 feet), and has four doorways facing North, South, East, and West. It now forms the base of a later Saxon tower.

Nearly all Saxon churches contained crypts, generally with two means of egress so that religious processions or pilgrims might enter down one stair and exit from another. Burial in church crypts or by the altar was naturally reserved for high ranking clerics (many of them soon to be saints) or outstanding patrons; Godgyfu (Lady Godiva) and her husband Leofric Earl of Mercia were buried in the Priory Church of St. Mary, St Osburgh, and All Saints which they founded and endowed in Coventry in 1043. (This small stone church no longer exists – it was replaced by a far larger church in the 13th century, then dissolved as a religious foundation by Henry VIII in 1539, and thus fell into ruin.)

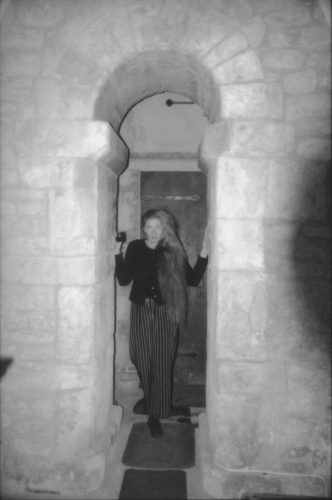

Godgyfu and Leofric endowed many churches, and the still-extant Priory Church of St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsay in Lincolnshire was among them. It is of particular interest as a significant portion of the beautiful and impressive church there issued from their hands. The earliest stonework in the church dates from 955; Godgyfu and Leofric greatly endowed and enriched it from 1053-55. The lofty crossing features four soaring rounded Saxon arches (which now enclose later pointed Norman arches built within the original Saxon arches). A 10th or 11th century graffito of an oared ship is scratched into the base of one of the Saxon arches, possibly a momento from a Danish raider who sailed up the nearby Trent. The north transept houses a narrow, deep Saxon archway of honey-coloured stone, which would originally have been lime-washed and over-painted with decorative designs.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. Three windows, three ages. The circular window is Saxon; the very narrow round-headed one beneath it is Norman; the larger pointed one later Medieval.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. The crossing. The later, pointed Norman arches were actually built within the larger rounded Saxon ones.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. North transept. Narrow Saxon doorway with your author inserted for scale.

St. Mary’s Stow-in-Lindsey. Ancient stone steps to tower.

The interiors of churches during this period contained no pews or seating. Worshippers stood in the nave facing the chancel in which the priest officiated.

St Marys, Deerhurst, founded 804. Early pointed windows high up in the west wall of the Saxon tower. Photo by F. H. Crossley

Windows could be very irregular in placement. Most windows of course were unglazed, although thin slices of horn made up small multi-paned windows, much as Ælfred devised a lantern protected from draughts using such a method. Window glass was being formed by Anglo-Saxon artisans by at least the 10th century (if we discount the Gaulish glaziers brought over by Benedict Biscop in the 8th century) and precious panes were also imported from the Continent.

Cement, Plaster, and Paint

Good quality stone amenable to hewing in dimensional blocks for building is rarely evenly distributed throughout the landscape. Fortunately human inventiveness honed through trial and error can make suitable substitution. Flints in mortar serve well as a building material where quality material such as limestone or sandstone is lacking. Once the art of making cement mortar was mastered fire-resistant construction was available even where dimensional stone was not.

Saxon cement mortar was quite strong, allowing masons to safely construct walls which were unusually thin and tall for the material. Ninth century mixing pits for the creation of mortar have been found near St Peter’s Church in Northhampton. Paddles attached to a huge timber cross bar centred on a vertical pin were turned when men pushed against the bar while walking in circles around the shallow mixing pit. Arduous work, but the resulting high quality cement was obviously worth the expended effort.

Mortar was used not only to affix stones to each other but in the creation of plaster. Many stone buildings had plaster exteriors as well as interiors. Plastered interiors in the case of churches were almost always decorated by figural paintings. These were uniformly over-painted during the Reformation (in many cases with scriptural verses), but still could have been recovered using modern techniques. Wrong thinking “restorations” in the 18th and 19th century stripped away nearly all of the extent plaster on Anglo-Saxon stone structures, including the remains of Anglo-Saxon wall paintings – a great and irreparable loss. Early restorers did not understand that the original builders of these churches meant them to be plastered and painted. They rashly chipped off centuries-old painted plaster to expose rough stone work that the generation who erected the buildings never intended to be seen. Still, a handful of fragments survive in a handful of churches to tantalize.

At any rate the painting of timber, stone, and plaster was commonplace. It is important to consider this when looking at the remaining Anglo-Saxon stone structures, or contemplating the reconstruction of a great hall. In the same way that it is hard for us to believe that the chaste white sculpture of Phidias was once painted in riotous colours when it adorned the Parthenon so must we allow our preconceptions to fall away while imagining Anglo-Saxon architecture in actual use.

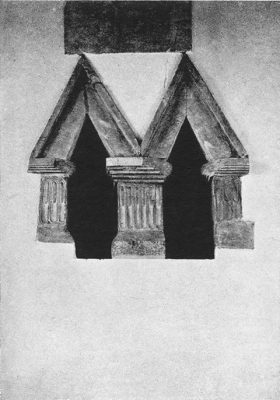

Stone carving was well evolved and many Saxon churches were embellished with stone sculpture and bas reliefs. Like so much from the era, what remains is very often fragmentary, and much sculpture was broken up and used as rubble filling in later construction. The juxtaposition of depicted scenes reveal a sophisticated knowledge of scripture and of contemporary religious commentary, oftentimes incomprehensible to later viewers.

Stone and wooden sculpture too (very little of the latter has survived) was routinely coated with gesso, painted with mineral paints in brilliant colours, and often had additional attachments such as gems of glass or metal work affixed to them. Paints included black, white, red, yellow, green and mixtures thereof. Iron oxides yielded red and yellow ochre, copper salts gave green, charcoal black, and lime brilliant white for highlighting. Painting not only gave life and colour to the stone, but could be used to correct any defects in the natural stone or in its carving. The painting of sculpture also allowed distinguishing elements such as special colours or even the names of personages included as means of identifying the subject.

Entire walls were painted by plastering over wood timber or wattle work or stone. The plastered wall was next lime-washed, readying it to receive mineral colour paints which were then fixed with casein made from skim milk. Apart from the beauty and liveliness they imparted during services, wall paintings in churches served as a Biblia Pauperum, “Poor Man’s Bible” illustrating episodes from scripture, scenes from the lives of saints, and allegorical lessons.

Sometimes the plaster itself was tinted either inside or out; in the case of the religious complex at Monkwearmouth the exterior plaster bore a pale rosy tint.

The End of It All

The Norman invasion of 1066 had an immediate and disastrous effect on Anglo-Saxon architecture. With the huge influx of Norman clergy following Hastings virtually every important English church was rebuilt or substantially altered. The great halls of now-slain ealdormen and thegns were taken over by Norman victors and altered to new tastes. Many existing structures whether sacred or secular were completely dismantled and their successor erected over the site. The necessity to subdue the populace led to the rapid building in stone of castles and other fortifications. But the Norman style of building in stone did not obliterate all timber halls in burh settings, and the Normans were quick to seize upon and make use of local forest reserves. The Saxon burh at Goltho described above was rebuilt by its Norman owner in the middle of the 12th century, using timber construction.

To see an excellent new timber hall in Lincolnshire built according to the principles of Anglo-Saxon architecture, click here.

Regia Anglorum is building a community near Canterbury in Kent in late Saxon style, including an impressive great hall which you can see here.

If you have enjoyed this essay you’ll also enjoy looking into some of the reference books I used:

Timber Castles, Robert Higham and Philip Barker, Stackpole Books 1995

Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Mary and Nigel Kerr, Shire Archaeology 1989

Medieval Wall Paintings, E. Clive Rouse, Shire Publications 1991

Winchester in Anglo-Saxon Times, Andy King, Winchester Museums Service 1993

Anglo-Saxon and Viking Life at the Yorkshire Museum, Elizabeth Hartley, The Yorkshire Museum 1985

The Mead-Hall: Feasting in Anglo-Saxon England, Stephen Pollington, Anglo-Saxon Books 2003

English Church Design, F.H. Crossley, Batsford 1948

The Anglo-Saxons, James Campbell, editor, Penguin 1982

The Meaning of Mercian Sculpture, Richard N. Bailey, Vaughan Paper No 34, University of Leicester 1988

That is also the story of how Brittain become latin catholic, it was mostly Orthodox Catholic at the time of the invasion, but as you refered the replacement of culture and clergy was fatal!

Should be expanded into a book. Well done you

Hello, Octavia. This was the last of the wonderful essays I’ve spent the last month reading. Thank you for putting together such excellent resources and source materials for further research. Now on to The History Quill! All the best, Lisbeth

Hi! I am trying to cite the “Fyrkat. A mid-20th century reconstruction of a Danish great hall and long houses in Hobro, Denmark. ” photo in MLA 9th Edition! Do you know the author/photographer of that photo? the title of the artwork in italics,

and the date of composition and the location of the institution for which this is published?

Thanks,

Hannah!

Leof Hannah (hailing you in Old English)

I don’t know the photographer of the photo in the book you mention, but you may use the one from my website, if that helps. The photographer gives his consent. If you use it please credit Jonathan Gilman. The photo was taken in 1999.

wes thu hal (be whole and hearty)

Octavia

Thank you so very much, Octavia! I will credit the photographer:)

wes thu hal,

Hannah

Wonderfully informative, thank you very much for sharing.

What were the actual size of the stone masons tools used in medieval or earlier times? Tools like the level , square and plumb line.

This is a wonderful work of love and art that you’ve made here, Octavia. It is brilliantly done, bravo!

Thank you for the wonderful piece on AS Buildings. I’m doing a piece for the family on the old Edwards (Edward the Elder, Edward the Martyr, Edward the Exile, Edward the Confessor), was trying to find some remaining structures from the era we could see today. You write very beautifully.

MLE, Abingdon, Virginia.

Many thanks, Michael. Early architecture is a passion of mine and has been since childhood. Very glad you found the piece useful. Little remains of buildings from Anglo-Saxon times, but what we have is fascinating…

How do we know about Anglo Saxon architecture?

We know from many sources, Dylan, even given the length of time that has passed. Firstly, from the remaining buildings themselves, from ruins and foundations, and building fragments. We gain information from period artwork, such as manuscript paintings, which depict buildings. We have written descriptions of some buildings too, in poetry and prose. So happily there are more sources than you might imagine to learn from about these structures.