Women’s Legal Rights in 9th Century England and Scandinavia: Why (Almost) Everything You Think You Know is Wrong

A talk delivered at Dragon Con, Atlanta, Georgia, 2 September 2018

I am Octavia Randolph, the author of The Circle of Ceridwen Saga, a series of historical novels set in 9th century England and Scandinavia.

IN our time together today we are going to be looking at what we know about the legal rights – and therefore in many ways – the activities and possibilities for women – in both the Anglo-Saxon and Norse world of the 9th century. This of course is the period of great contact – and friction – between the Saxons and Norse, particularly the Danish and Norwegian raiders we call Vikings.

First, a word about nomenclature. I will use the terms English, Anglo-Saxon, and Saxon interchangeably today to designate the people groups inhabiting what were the 9th century Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. I will use Norse and Scandinavian also interchangeably; and because it is a useful shorthand, I will also use the term Viking.

I would like to stress though that the word Viking was not at all what the Anglo-Saxons called the raiders who landed and wreaked so much mischief. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which is the main source, and a very reliable one, for the history of the time, refers to the raiders by three names, and three names only: The Danes; The Great Army; and (my personal favourite) the Heathen Horde. “Viking” was unknown; and it is actually a quite unusual word in Old Norse. A vik is a bay or stream, and one can readily imagine the narrow, shallow-draught drekars – dragon ships – of the raiders taking advantage of such waterways; but as a noun Viking is very rarely recorded. To go “a-viking” – to go raiding – is a bit more usual.

So.

It’s a confusing landscape out there. Hollywood shows us sword wielding “Viking women” on the one hand, and on the other we may in quieter moments reflect on how fortunate we are to be a millennium away from the limited roles and rights of our fore-mothers. So let’s prod a bit.

What do we think we know?

Here in the 21st century it is easy, and even natural, to believe in an ever-improving continuum of human rights. (Hey, now that it’s 2018 even women can legally drive in Saudi Arabia.) We look back to the banning of slavery in Britain in 1834, the signing of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States in 1865, the granting of the vote to women in Australia in 1902, in the US in 1920, Scandinavian women between 1906 and 1921, and in Britain in 1928. We look at the passing of Civil Rights laws in the 1960’s, recent legal recognition of same sex marriage in many nations, and feel: “This is the natural progression of things. People gain more rights as time goes on.”

But you might be surprised to learn that if you are of English descent, your maternal ancestors of 1000 years ago enjoyed more legal rights than did your great grandmother. Shocking, but true.

Women’s legal rights under, say, King Ælfred the Great (who was King of Wessex, and died in 899) were far greater than under Queen Victoria (who reigned from 1837 to 1901). Indeed, the Victorian era was the nadir of women’s rights in Britain, as women were reduced to the state of near-complete legal dependence on fathers and husbands, and divorce became ever more restrictive, until it required an act of Parliament, right up until 1857. Victoria, the most powerful woman in the world, repeatedly claimed her own sex unfit to win suffrage. But that is another story…

The fact is that women enjoyed legal rights under Anglo-Saxon law that they were to lose after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and for many hundreds of years afterwards. So let us return to the more congenial 9th century, and learn more.

We know a lot about the rights and responsibilities of Anglo-Saxon women because so much textual evidence has survived, in the way of laws, wills, poetry, and even riddles, all of which add something to our picture of the lives and scope of women of the era. Ælfred’s own 9th century law code has survived, and provides us with valuable insight into women’s legal status.

Ælfred’s laws cover penalties owed for kidnapping (or luring) a woman from a nunnery; for assault, sexual and otherwise, of a woman; rape of a slave woman; rape of underage girls; and for the death of a pregnant woman. While it is true that the financial penalties exacted from the wrongdoer typically went to the women’s father or husband, it is also true that crimes against women were treated with as much seriousness as crimes against men.

And no woman of any age could be forced into marriage:

No woman or maiden shall ever be forced to marry one whom she dislikes, nor be sold for money.

Other rights that Anglo-Saxon women enjoyed were the right to own land in her own name, and to sell such land or give it away without her father’s or husband’s consent; the right to defend herself in court; and the right to act as compurgator in law suits; that is, to testify to another’s truthfulness. She could also freely manumit her slaves. Her morgen-gifu, or morning-gift, that gift of land, jewellery, livestock or other goods that a bride received from her new husband the morning after their wedding, was hers to keep for life, and if she died without children it went to her own people, not to her husband. (Compare these rights to those of your great grandmother in London, the chattel of her father until marriage and then the legal “property” of her husband afterward.)

One of the greatest indicators of women’s rights is the woman’s ability to end an abusive or otherwise unsatisfactory marriage. Divorce was extremely common amongst upper-class Anglo-Saxons; indeed – and to the chagrin of the Church – both men and women practiced serial “marrying up” as a form of social climbing. (More humble folk simply separated without ado, to take up with another, or remain single as they wished.)

Early English divorce laws granted the wife anything from one third to all of the household goods, depending on which kingdom she lived in.

This included any goods she had brought into the union, and she typically received full custody of the children. But if her husband wanted full custody of the children, he was to pay her for that right, the equal to the child’s inheritance share. If a woman’s husband was convicted of theft and his goods were confiscated, hers could not be touched.

In the 9th century daughters inherited goods or land from either parent, or both, and these bequests were theirs without challenge or question.

English women could rise to great rank in what we might normally think were male spheres; it was not at all uncommon for an Abbess to rule a doubled foundation, that is a conjoined monastery and convent. Ælfred’s own daughter, the immensely talented and skilled Ætheflaed, ruled the Kingdom of Mercia with distinction for seven years after the death of her husband, directing its military defence and successfully repelling waves of Danish invaders.

This relative liberality of women’s rights came to a crushing end after the catastrophe of October 1066 at the Battle of Hastings. The Normans (“northmen”) carried across the Channel with them the vestiges of their earlier mores towards property and women. A legal “golden age” for English women had come to an end.

The legal rights of Norse women during the Viking age are altogether more difficult to ascertain. As Judith Jesch states in her ground-breaking book of 1991, Women in the Viking Age, we know “very little, if anything” about the legal position of women, as the source material we do have – high medieval Scandinavian laws and the Icelandic Sagas – are products of a far-later time, and reflect Christian norms. Remember that Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson, who wrote down the Prose Edda, which is just about everything we know of Norse mythology, was writing long after the era – he died in 1241 – and he was writing through a Christian lens.

We simply don’t have the wealth of written material we have about English women, and much of that is due to the fact that Anglo-Saxon scribes had both Old English and Latin to record such matters with, and had pen and ink and parchment on which to do so. Norse peoples had runes cut with knives and chisels into wood and stone – a cumbersome, time consuming and bulky method of recording anything.

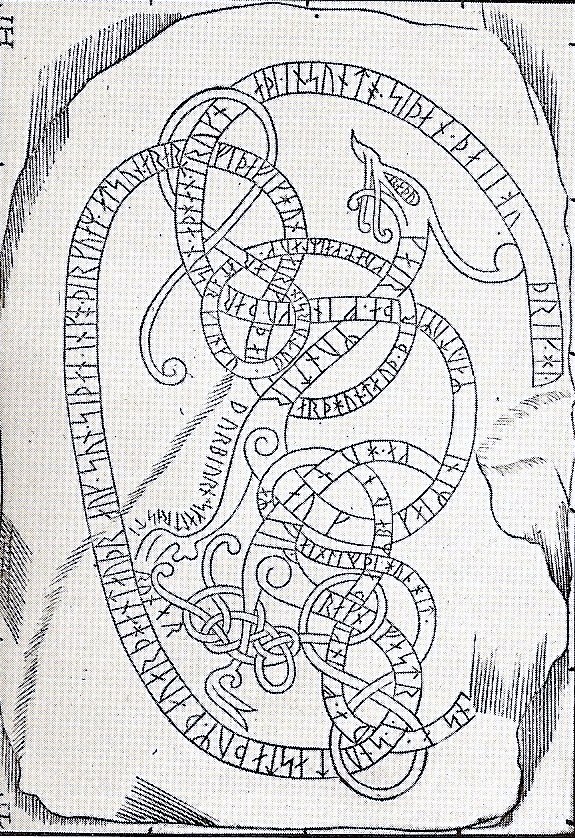

Nevertheless, four related Swedish rune stones tells us more than we know about Norse law than almost any other source, as they record a complicated line of inheritance of a farm in Uppland. The stones were paid for by a woman, Inga, in honour of her first husband, Ragnfast – and many Norse women undertook the cutting and raising of rune stones, in memory of loved ones. From Inga’s rune stones we learn that a man did not inherit from his wife. Children could inherit from parents, and parents from children, if the children died first – but men did not inherit from their wives. A wife’s property apparently stayed in her own family; in the case of Inga’s family, when Inga’s first husband Ragnfast died, his wealth went to their child; then the child died, and it went to Inga. When she died, her second husband Erik received nothing; her wealth went to her own mother.

Image 1: the Hillersjö rune stone, one of four telling the story of Inga’s inheritance. Drawing: Johan Hadorph – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.

Given the property rights of Norse women, we might almost consider them as equals to their Anglo-Saxon sisters. They were not. Norse women were forbidden to speak at legal assemblies, or to testify before a court. These two points are huge. Remove legal agency from a person, render her by reason of her sex to be unable to be a compurgator – to attest to another’s truthfulness – reduces a woman to a child-like state, someone not to be believed.

A Norse woman could only be head of her household if she had no male relatives living, but if she married, those rights were transferred to her husband. When a young woman reached the age of twenty and was still unwed she was allowed to decide her place of residence, if she wished to leave her birth family; but she had no right to choose her husband. We’ve seen that under Ælfred’s laws no woman could be forced to marry, but marriages for women in both cultures, particularly for those with land and silver, were typically alliances, decided by the families.

It is true that heathen Norse women could, like Christian English women, easily divorce their husbands, and must be dealt with equitably when that occurred. A Norse woman could merely call witnesses to her home and before the marriage bed proclaim the dissolution of her bond of matrimony.

But polygamy was a one-way street in the Norse world. A Norse man had the right to take as many wives as he could afford – but women were always limited to one husband. Anything approaching equality of the sexes is impossible with such duality.

The Icelandic law code known as Grágás is quite explicit about sexual roles:

If in order to be different a woman dresses in men’s clothes or cuts her hair short or carries weapons, the penalty for that is lesser outlawry. (that is, banishment for three years) It is a summoning case and five neighbours are to be called for it at the assembly. (And these neighbours must all be men…) The case lies with anyone who wants it. The same is prescribed for men if they dress in women’s clothing.

Caring for household and farm was always demanding work. Yet Norse women did also act in what we might consider traditionally male spheres. We have the name of one Norse female rune cutter – and if one existed there must have been more; we know of two professional female poets; and women were active in trade, certainly, we have sets of weights and scales as grave goods to prove it.

Eva-Marie Göransson, in her 2002 study “Images of Women and Femininity on Gotlandic Picture Stones” points out two examples of women acting in traditionally masculine activities.

Image 2; map showing Gotland. Google Maps

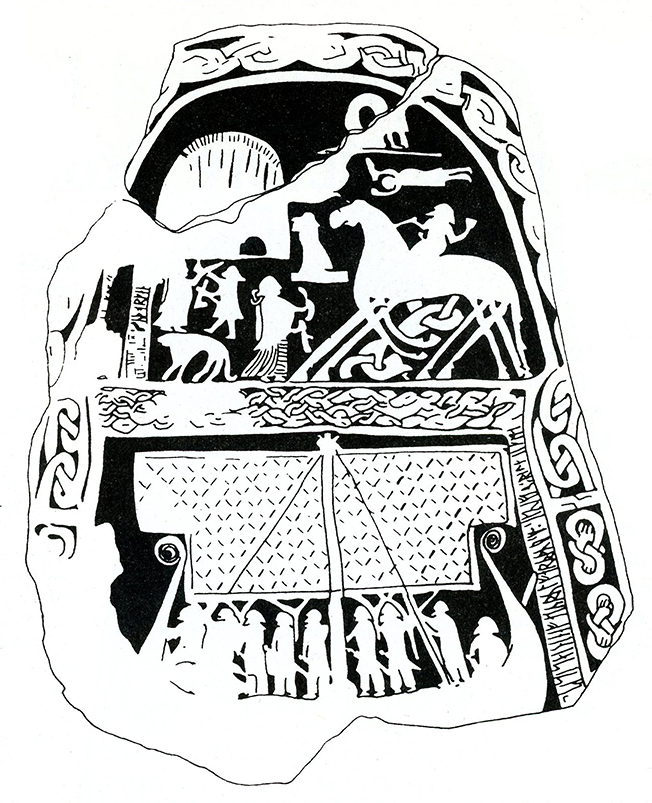

Gotland is a small island in the middle of the Baltic, famed for its rich material remains from the Bronze and Iron Age. (It’s also where I live.) Its large standing stones, richly decorated with pictures, form a major source for our pictorial knowledge of the Viking Age.

Many of these stones are extremely tall; here’s a photo of one in the museum there, with me inserted for scale.

Women are easy to discern on the stones; they wear triangular shawls and sport long pony tails.

Image 4: Odin being greeted. Drawing of Tjängvide picture stone by Eva-Marie Göransson, published in Viking Heritage Magazine 1/2002

Here is a drawing of one of the stones, showing a typical “shield-maiden” welcome. We know this must be Odin arriving, as he rides his eight legged horse, Sleipner. He is being greeted by a woman holding out a drinking horn.

This kind of activity is often seen on stones – a woman greeting a male warrior with a drinking horn.

Image 5: Drawing of Levide picture stone by Eva-Marie Göransson, published in Viking Heritage Magazine 1/2002

But on the two stones pictured here we have two women, greeting female waggon drivers with the same ceremony. These are from two Gotland picture stones, one from Levide and one from Grötlingbo, showing women driving waggons, and even more interesting to me, being greeted by another woman with a “welcome” drinking horn.

Image 6: Drawing of Grötlingbo picture stone by Eva-Marie Göransson, published in Viking Heritage Magazine 1/2002

Waggons of course are identified with death and being carried to the afterlife, so perhaps this could be a kind of “shield-maiden welcome” in itself.

What else do we know about the status of women? From studying grave remains, both Anglo-Saxon and Norse women were less adequately nourished in childhood than were their brothers, and girls suffered from more anaemia and dental disease because of it.

Now, a large question:

Were there female warriors in Viking Age society? Though relatively few historical records mention the role of women in Norse warfare, a 10th c Irish text notes a female warrior known as Inghen Ruaidh (“Red Girl”), leading a Viking fleet to Ireland. Johannes Skylitzes, 11th c Greek historian, wrote of women fighting with the famed Varangian Guard in a battle against a Bulgarian host in the year 971. We have the highly romanticized and unreliable account from the Christian theologian Saxo Grammaticus, who about the year 1200 shares the story of the woman warrior Lagertha, who he tells us was wed to and divorced from Ragnar Lodbrok.

A word about unreliable accounts: this would be an account that is unique, that has no other corroborating reporter also telling us the same (or similar thing), and which also has no archaeological evidence to substantiate it. And just about everything Saxo says about women warriors falls into these categories.

Saxo compares Lagertha to the Amazons, those (real) Scythian female warriors who the ancient Greeks admired, and even feared. Saxo created a number of female warriors to use as object lessons in his Gesta Danorum, and was writing long after the era he purports to record; Ragnar Lodbrok (who was likely real, or at least a composite of real warriors) was said to have died in 865, so over three hundred years had elapsed, and Saxo is the only one who tells the charming fiction of Lagertha’s story.

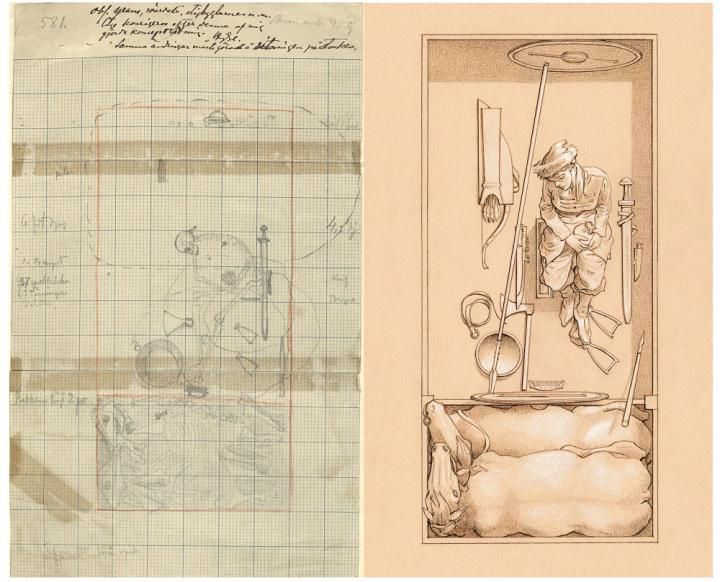

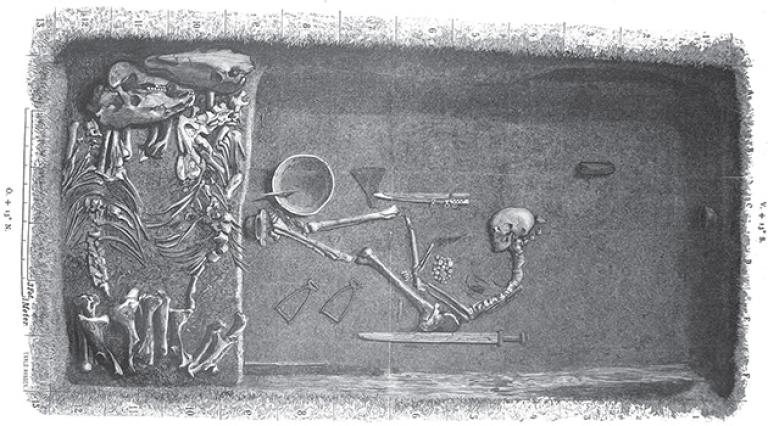

But: Many of you have seen the 2017 conclusions of DNA testing affirming that a 9th c burial at Birka, Sweden with weaponry was indeed that of a woman. It is an exciting and eye-opening report. This grave, known as Bj581, is one of 3,000 known burials at Birka, an important Viking-era trading post. The grave Bj581 was a particularly rich one, and has been well documented. All except for its inhabitant.

Two scientists making careful study of the remains have finally established the sex of the inhabitant of this grave. A rigorous examining of the skeletal remains of pelvic bones and jaw by bioarchaeologist Anna Kjellström at Stockholm University pointed firmly towards a female verdict. Then at Uppsala University archaeologist Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson extracted two types of DNA from the left canine tooth and left humerus. If the bones studied indeed belong to this grave – and chances are pretty good they are – this burial was indeed that of a woman. But they might not be – the bones were removed from the grave almost 140 years ago and things can get jumbled.

Image 7: This reconstruction of the Birka grave site shows how the woman may have originally been buried. (Þórhallur Þráinsson ©Neil Price)

It is certainly true that faulty attributions of grave inhabitants have been made over the centuries. Lacking complete skeletons (or in the case of cremation burials, any skeletons) grave goods could lead archaeologists and scholars to false ends. (The Birka find, though quite complete, was excavated in the late 1880’s). If cooking implements were found, an assumption of a female grave might be made, completely overlooking the fact that male traders and raiders had to self-cater, and carried these things with them. The Birka grave held a sword, battle axe, spear, shield, arrows, and two sacrificed horses (mare and stallion, so they might increase in the afterlife) – and the body of a woman. Also, on her lap – signifying her role as tactician, or as a more playful touch – gaming pieces from tæfl, a strategy board game.

Another interesting fact is that she was quite a tall women by her standards – 5’5”. A mass grave site in England of Danish warriors and their Danish wives – victims of contagion – tells us the average Danish Viking was about 5’7”, and his wife 5’1”. So this women, of about 30 years of age, so nobly sent to the afterlife, was rather a commanding figure at her height.

Hunting equipment, weaponry, and tools for wood and metal working have been found in women’s graves before. But there was perhaps a symbolic aspect to any grave goods – men, just by being male, would be equipped with spear and shield to protect himself in the next world, even if he had never done so in this one.

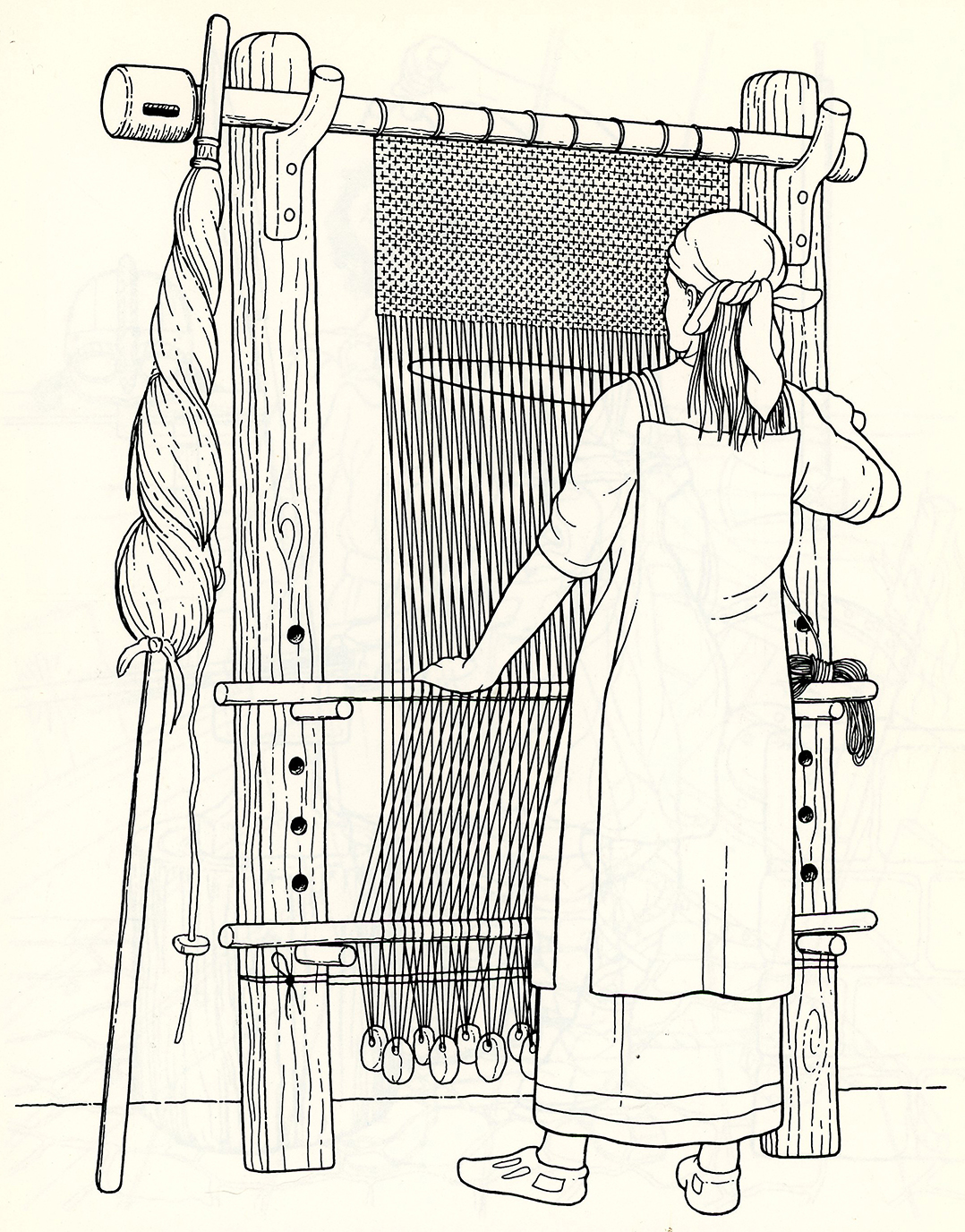

And to complicate matters, sometimes a sword is in fact not a sword. It might be a weaving sword – a batten of iron used to compact the woof – the active thread – against the warp – the foundational substrate on the loom.

Image 8: floor loom and weaving sword. Drawing from Story of the Vikings Coloring Book, A.G. Smith, Dover Publications

Lorraine Evans (Wiðowinde No 132, Winter 2003) has done a study of iron weaving swords found in female graves in England, France, and Germany, finding them to be identical but smaller versions of battle swords – 15 to 19 inches (40 to 50 centimetres) in length compared to 32 to 38 inches (90 to 100 centimetres) for a battle sword. Some were cut-down swords, others forged to a shorter length.

As a weaver, I would only use such an iron batten if I were weaving very dense, hardy fabric, such as the thick and durable wadmal which was a major export of the Norse. It was a dense, felted woollen used for mantles, alcove curtains, and blankets; nothing glamorous about it but valuable in its own right.

So there is a distinct possibility that these iron swords found in women’s graves might be symbolic and ceremonial; or they were using them as weaving battens with heavy fabric.

Another fact to consider is that most of these weaving swords are found in high-status graves, those with considerable grave goods in silver, crystal, and even gold. So status is denoted in the possession of an iron sword, even if it is used for tamping up the woof.

But to return to the occupant of grave Bj581. Why would a woman be buried with such weapons, if she was not using them? One must remember the tremendous material value and ritual significance of weaponry, in both Anglo-Saxon and Norse culture. Even onlookers were aware of this; the Roman historian and senator Cornelius Tacitus, in his report Germania, completed about the year 98, notes that women not only could receive weaponry as a dowry, but were expected to preserve and protect it for coming generations.

Image 9: Birka grave Bj581. Illustration by Evald Hansen based on the original plan of the grave by excavator Hjalmar Stolpe, published in 1889. Uppsala University

So who was this woman, buried in Birka, with such great war trappings? It is tempting to imagine her as one who wielded these weapons with honour and courage, and with success.

But this is where we run into difficulties – for we must face the grim realities of hand to hand combat, body weight, upper body strength, and every other factor that weighed in any warrior’s survival from battle to battle.

If it is true that the bodies of dead women warriors were found amongst Germanic tribes warring against the Romans, they were likely fighting out of real desperation, and were not normal troops. Woman just can’t fight in hand to hand combat with spear and sword against men and have any real chance of survival.

We know from both textural reports and contemporary illustrations that smaller men, younger men, did not take part in the shield walls directed by Saxon war leaders. Stronger, bigger men fought hand to hand with shield and sword or shield and spear. Smaller men flung throwing spears, and hurled missiles like round river stones in leather slings. And smaller men were archers.

This is indeed one of the great levellers: archery, and horses. (And this, in fact, is where the formidable Amazons come in – they were superb equestriennes.) Men and women fighting each other with bows and arrows on horseback is a much fairer contest. And women on horseback with bows can inflect great damage on ground troops, as it is hard to withstand repeated onslaughts of arrows; one can’t advance, and one can’t open the body enough to fling a spear, if the enemy comes within range.

We may never know how the Birka Woman used her weapons, but I admire her for having them. But perhaps like me, you’d like to be astride a horse, bow in hand…

Portions of this piece were previously published on octavia.net

Marvelous read & gratifying research. Thanks for re-posting it.

Sorry I missed your Virtual Library talk yesterday. I’ll try to see if it’s still available.

Thank you some much, this has made is easier for me too under stand this time in history as l do a medieval fest in Australia, and to get my stall l have to keep it as of the time.

Thank You!for sharing this wonderful information.

Thank you, Octavia, for this wonderful, detailed study! I’ve read all the Ceridwen Circle books and so very eagerly await the next. (What news she has for Sidric; what he must tell her, etc.). Thank you for her whole story!

Thank you Octavia this presentation is very informative and interesting. Reading I am imagining the female characters in the series and seeing these pillars along the shores of Gotland. Thank you

Thank you so much for generously sharing this with you! I am loving your books. All of them. I still have to read on the one about Light, but I will…first I am lost in the land of Sidroc!

Happy New Home!!!

Linda

https://coloradofarmlife.com/

I absolutely love this, Octavia! Thank you for sharing your wonderful talk with us and as usual, giving a great history of our heritage!

Octavia, You raise the bar once again with your knowledge and resources. I love your saga series I’m reading Ceridwen again. This is fascinating as I read your presentation I’m reflecting on how I was raised as a woman. I have Swedish ancestors and have only attained the 5’1″ stature, i am good with a bow, now thinking of changing my viking dress to express the warrior in me. Thank you so much for Ceridwen Saga and our Saga facebook group and all you share. Gotland will soon find the treasure you are. Blessing on your new home. Dragon Con 2019 Saga sisters!

Thank you, Octavia for sharing. As usual I’ve enjoyed and there is always something in your writings that I learn and want to explore more.