Domesday Book

Domesday (Dooms-day, Judgment Day) received its name in the 12th century, for it was regarded as the ultimate authority, the last word on matters of property. Domesday is a most remarkable and valuable record, created in 1085-1086 by order of William (“the Conqueror”), so that he might fully know and understand the nation he ruled over. It is still considered admissible legal evidence in England today, having been cited in court actions several times in the twentieth century.

Domesday Book. www.bbc.co.uk

Anglo-Saxon shire administration was quite advanced by the turn of the first millennium, with shire boundaries which remained little altered right up to 1974. However, nearly twenty years after William defeated the last Saxon king, Harold, at Hastings (1066), William embarked on an undertaking the scale of which had never been attempted: to gather detailed fiscal, ownership, and tax information into one format. The record tells that at his Christmas court in 1085 he

…had much thought and very deep discussion about this country – how it was occupied or with what sorts of people. Then he sent his men all over England into every shire and had them find out how many hundred hides there were in the shire, or what land and cattle the king himself had in the country, or what dues he ought to have in twelve months from the shire. Also he had a record made of how much land his archbishops had, and his bishops and his abbots and his earls…(Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Anne Savage translation)

To accomplish this he sent commissioners into 35 shires, asking, Who owns this land today (in 1085)? What is its worth? Of what is it comprised? Who owned it in 1066? What was it then worth?

The results, collected with astonishing rapidity, were inscribed into individual quires, one for each county. Here is a typical entry, from Oxfordshire:

Islip: Roger d’Ivry’s wife holds 5 hides in Islip Letelape from the King. Three of these hides never paid tax. Land for fifteen ploughs. Now in lordship 3 ploughs; 2 slaves, 10 villagers with 5 smallholders have 3 ploughs. A mill at 20 s.; meadow, 30 acres; pasture 3 furlongs long and 2 wide; woodland 1 league long and 1/2 league wide. The value was £ 7 before 1066; when acquired £ 8; now £ 10. Godric and Alwin held it freely.

One can see at once the value of such detailed information: the size and type of holdings (meadow, pasture, and forest), its owner (the here-unnamed Azelina d’Ivry), how it was acquired (seized by new-king William from the Saxons Godric and Alwin, who had owned it outright in 1066), the number of slaves and farmers, the mill assessment, the number of ploughs used to farm (although the arable land is estimated at 15 ploughs worth, only 6 ploughs are now being used). Entries of other estates list further details such as number of sheep, goats, swine, and cattle.

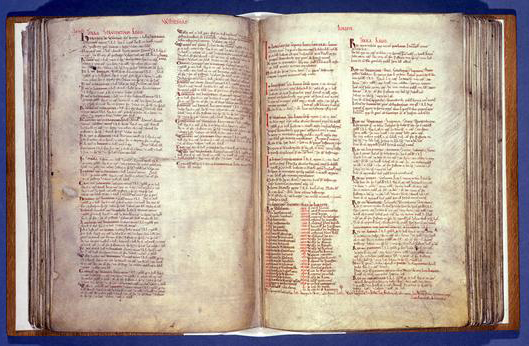

Domedsay was written on parchment, in dark and red inks, and in Caroline miniscule script, very attractive to the eye. Slightly later the individual quires were bound into two thick books, which today are in the keeping of Public Record Office in Kew, London. Although few scholars are allowed to see the originals, a handsome facsmile is on display in the lobby of the building.

Not every portion of England was included in Domesday. Possibly because their resources were already well documented, William did not order such a survey for the longtime Anglo-Saxon capitol city of Winchester, nor the newer, Norman capitol of London.

The Latin used in Domesday is almost indecipherable to all but Domesday scholars, as the scribes, to save space, adopted an extreme Latin shorthand. Beginning in 1969 work was begun on a modern English translation. Today Domesday is so available, in its original individual shire-by-shire format, from Phillimore & Co. Ltd., Chichester, West Sussex, PO20 6BQ, England. A most attractive overview is offered in The Domesday Book: England’s Heritage Then and Now, edited by Thomas Hinde (Coombe Books 1996).