Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry

“Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry” created in Reading, England in 1885

One of the treasures of the attractive Museum of Reading, Berkshire is a full-length replica of the Bayeux Tapestry. Dubbed by the museum “Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry”, it was created in 1885 by a group of industrious English needlewomen. Few know that this copy exists; the sophistication of the modern gallery viewer, general lack of interest in history, and a sort of bemused embarrassment concerning the value of replicas make the validity if not the existence of such an item rather problematical both for the owning institution and the visiting public. But the student of Anglo-Saxon studies and anyone interested in either needlework or the neo-medievalism of the Victorian era will relish the experience of seeing it.

The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry

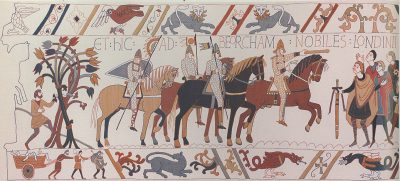

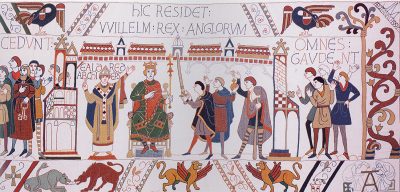

Housed in the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux at the Centre Guillaume-le-Conquérant in Bayeux, Normandy, is the Bayeux Tapestry, not a woven tapestry at all but instead a 230′-9″ (nearly 70m) strip of linen averaging 18 to 20″ (46-51cm) in width. A version of the momentous events of 1066 is embroidered in woollen threads upon its surface. The tale of the death of Edward the Confessor, the visit of his heir Harold to France, his subsequent accession as the last Saxon King of England, and the battle of 14 October 1066 are all told in exuberant and colourful detail. The narrative ends abruptly on the field of battle; originally the final scene must have been that of William’s jubilant coronation. But the loss of this closing episode in no way mars the remainder. A tumult of activity, personalities, and scene changes spill across its length, and draw the viewer in with the verve and immediacy of the draughtsmanship and the boldness of colouration of the figures as they journey to an inexorable end. It depicts 623 people, 202 horses and mules, 55 dogs, over 500 other beasts both real and mythological, 37 buildings, 41 ships, all crowned by a running commentary in Latin describing the scenes as they unfold.

No records remain to tell us who commissioned this remarkable feat of needlework, who created it and when, or where it first hung, but modern scholarship is in agreement that the commissioner was probably William’s own brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux. This warlike and womanizing cleric figures prominently throughout the piece. Jan Messent in her incisive book The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers’ Story argues persuasively that the intended setting for the embroidery was the newly enlarged royal residence at Winchester, and that the embroiderers were the inmates of six or seven Wessex nunneries: Winchester (long famed for its needlework), Wherwell, Romsey, Wilton, Amesbury, Shaftesbury, and possibly Barking in Essex. The work must have been carried out shortly after the victory when the episodes and personalities were still fresh in memory. Cloistered nuns, most of notable if not noble lineage, and all skilled with the needle, would have worked to a design approved by Odo.

Bishop Odo on the attack in the Bayeux Tapestry

The fine quality of English needlework was already renowned throughout France, and it would have made sense for Odo to utilize the most talented workers he could procure to execute such an important and costly project. Indeed, the memorializing of heroic lives and fierce battles in just such a manner was an English tradition. Byrhtnoth’s widow Æthelflaed gave to Ely Cathedral a hanging depicting the life of her husband, cut down at the battle of Maldon in 991, although sadly no remnant remains of the work.

Such was nearly the fate of the Bayeux Tapestry as it dipped in and out of obscurity. Numbered amongst the treasures of the Cathedral of Bayeux in an accounting of 1476, it was nearly cut up for use as munitions waggon coverings in the 18th century. It was rolled up on a wooden roller for some time before finding a more suitable home in the splendid Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, where it is now visited by many thousands each year.

You probably know that the Bayeux Tapestry ends abruptly. The final panel(s) have been lost for hundreds of years. These photographs represent the completing panels as imagined by artist, scholar, and expert needle woman Jan Messent. Photos used by permission.

Few people have viewed these magnificent, imagined reconstructions of how the Bayeux Tapestry may have ended. I am grateful to Jan Messent for permission to share these beautiful images with you.

The Reading Replica

The year is 1885 and the place London. A prosperous couple is being shown around the galleries of the South Kensington Museum (later to become the V&A) by its director, Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen. Knowing of the couple’s interest in textiles, and particularly the lady’s in embroidery, he escorts them to a private office where he reveals a sheaf of crisp photographs showing the Bayeux Tapestry in its entirety. Accompanying these are coloured drawings keying in the vivid hues of thickly laid wool upon the linen surface. The woman is at first stunned, then inspired. “England should have a copy of its own,” is her response.

The couple were Elizabeth and Thomas Wardle, who had travelled down from their home in Leek, Staffordshire, to take in the glories of the capital. Cousins bearing the same surname, the two had wed in 1857 and their affectionate marriage had yielded fourteen children. The family business was fabric dyeing; Thomas’s father Joshua had been a successful silk dyer in Leek, and Thomas carried on the work in his Hencroft Dye Works. Thomas travelled extensively throughout India to procure silks and perfect its dyeing, and produced highly popular needlework kits on silk that were snapped up by Victorian women eager to create “art needlework” to adorn parlour and boudoir. What distinguished Thomas from any other entrepreneurial businessman was his interest in craft. The new coal-tar and benzene based aniline dyes introduced from the 1850’s had so revolutionized dyeing that within a generation the craft of using naturally derived plant materials had nearly vanished. The great designer William Morris, champion of artisanry and the dignity of handwork, approached Thomas in 1875 to help recover some of the lost techniques of herbal dyeing. Thomas’s brother George was a manager at Morris & Co, Morris’s firm in London which designed and produced wall coverings, carpets, fabrics, and stained glass windows amongst other items, and likely brought the two together. In response to Morris’s proposal that the two attempt to relearn the art of natural dyeing, Thomas dedicated one of his two dyeing sheds at Hencroft for two years of experiments and production. Morris himself was often in residence in Leek, working over the dye vats. During the two years of their closest association Morris may have actually stayed with the Wardles; certainly his philosophies and values would have been attractive to Elizabeth.

The time was right for any artistic expression of medievalism, whether in buildings, furnishings, literature, or paintings. Growing interest in medieval or indeed any post-Classical studies made movements such as the Gothic Revival possible. Rampant nationalism during the height of Great Britain’s imperial powers made looking back on a lost era of heroic endeavour attractive, especially at a time when the Empire was showing signs of strain. Morris himself wrote reams of poetry on medieval topics, including a translation of Beowulf and reworkings of Icelandic sagas. With such a social backdrop it is no surprise that Elizabeth Wardle conceived the bold plan to copy the iconic textile of the defeated but proud Anglo-Saxons.

Elizabeth was a needleworker of acknowledged skill and taste; what is more she was a tireless organizer and able to instill enthusiasm in others. She was already highly experienced in large scale embroidery projects worked with other women, having completed a number of alter frontals and other ecclesiastical hangings. By 1879 she was at the centre of a group known as the Leek Embroidery Society (sometimes School) which created finished embroideries for individuals and churches and later produced kits using her husband’s silk fabrics and threads.

So both Thomas and Elizabeth were well suited to Elizabeth’s ambitious plan. Thomas would take charge of dyeing the 100 pounds of wool required, using such natural dyestuffs as madder, a source for reds, woad for blues, walnut roots for browns, and weld for yellows. The wool was dyed in eight shades to match those of the original embroidery in Bayeux: red, blue-green, sage, buff, grey-blue, dark blue, dark green, and yellow.

Elizabeth marshalled the 39 women who would participate in the re-creation. One of these, Miss Lizzie Allen, performed the onerous task of tracing on linen from the photographs provided by Cunliffe-Owen, and another was responsible for stitching the individual panels together. Two other women pressed the panels prior to their being joined and in other ways contributed to the effort. Thirty-five women took part in the actual embroidery, completing sections ranging from six inches to nearly twenty feet in length. Like the original, the work is effectively done in only two stitches, one a simple stem stitch used to outline areas, and the other laid work, in which wool thread is run back and forth over the front of the linen in dense areas and then pinned down with short stabbing stitches that fasten the wool firmly to the surface.

Most of the women were from Leek, and nearly all must have worked with almost superhuman effort, for the replica panels were finished, sewn together, and placed on display in the Nicholson Institute, Leek, by 14 June 1886. That a 230-foot embroidery could have been created in approximately a year from start to finish is a testament to the Society’s determination. It also offers a fascinating insight into how long the original may have taken to complete. If as Jan Messent suggests the Bayeux Tapestry was the work of six or seven English convents, most within ten or fifteen miles of the next, the conditions under which it was created were not dissimilar from those shared by Elizabeth Wardle’s dedicated band of local women.

Although great care was taken by Elizabeth to make her replica as close as possible to the original, there are two important distinctions. The first is that the women of the Leek Embroidery Society were determined to escape the anonymity that befell the needlewomen of the eleventh century. To this end they attached a handsome blue linen border to the top and the bottom of their replica. The top portion of this narrow border is blank, but the bottom portion, roughly 2 1/2″ (6cm) in width, contains each embroiderer’s signature. The very first panel, over 8 feet long, was fittingly executed by Elizabeth Wardle herself, and under it reads in coloured thread “Elizabeth Wardle’s work” (then a long graceful line of scrolling needlework) “ends here”. This opening panel was the first of two Elizabeth worked. Each woman adopted a distinctive way of signing her piece, with her own style of floral or scrolling designs running the length of the lower blue border. Some women preferred to work together; one densely-packed four-foot section was stitched by three women. One Anne Smith Endon was particularly energetic, creating nearly twenty feet of the embroidery in two panels. Like the original, the varying skills and perhaps even temperaments of the Leek stitchers can be discerned. Not all pieces are of equal quality, and even for a group of women accustomed to large projects it may have seemed overwhelming at times. Perhaps this is why “E. Eaton” could only complete six inches of embroidery, but her name is rightly emblazoned upon the blue border beneath those painstaking six inches.

The second way in which the Reading Replica differs from Bayeux Tapestry is both regrettable and wholly understandable. A certain amount of graphic editing was deemed necessary by the Leek ladies; whether the decision was made by Elizabeth Wardle, by the tracer of the photographs Miss Allen, or, as the Reading Museum website now suggests, through censoring by the male staff at the South Kensington Museum who provided the photographs – or a combination of influences – will never be known. In every instance in which human male genitalia is depicted in the original, it was omitted in the replica. The same fate was even suffered by many of the horses the Leek ladies stitched, so notably stallions in the original and neutered by Victorian sensibility in the later effort. It is clear that many of the Leek ladies were quite young women at the time they worked on the replica; they signed their names with their birth names and are later noted in Leek Embroidery Society records as becoming “Mrs So and So.” Yet a sense of delicacy so great that piquant elements serving as actual commentary on the main themes of the story were omitted (not to mention the absurdity of the debased stallions) seems pointless when the horrific violence of the battle scenes and Harold’s death is so graphically and accurately copied. The Leek ladies had sadly forgotten their Anglo-Saxon fore-sisters — very likely nuns and some of them invariably virgins too — who with a healthier view of sexuality, both human and animal, had no such compunctions.

This is why one wishes to cheer upon closely examining the work of a Miss Margaret J. Ritchie. She was entrusted with embroidering the important panel bearing the legend “Where Æfgyva and a certain cleric” depicting a now obscure sexual scandal between a young woman being lured from a nunnery by a tonsured priest. The cleric was likely Odo himself. Beneath this panel (or associated with it) as part of the small border tableaux of the original are three naked male figures in a state of arousal. In the Leek version, these men are blandly nude. But if one looks closely at the crouching male in a full frontal pose just beneath the Æfgyva scene, one can see Miss Ritchie’s dilemma, and her integrity. The tracer of the design has drawn in a pair of shorts on the offending figure. Miss Ritchie had to have been aware of the dishonesty of this amendment, for she refused to colour in the shorts with laid work or even to outline them in stem stitch. Miss Allen’s three pencil lines at waist and thighs remain, mute testimony to Miss Ritchie, a needlewoman who if she could not bring herself to follow the original at least would not implicate herself in a modern debasement.

Reading Bayeux Tapestry. The naked man “in shorts” is along the bottom border the second to the last image.

Subsequent History

The replica was received with general acclaim, and the Leek Embroidery Society set about attempting to recoup their financial investment by sending it around the country to be enjoyed by paying viewers. It even travelled abroad to America and then Germany. But no permanent home could be found for it, and the admission fees could in no way serve as adequate recompense for the labour invested by members of the Society. It came to Reading to be temporarily exhibited in June 1895, and during that time a former mayor and current alderman of Reading, Arthur Hill, offered to buy the replica and present it as a gift to the Borough. Elizabeth had her misgivings about allowing the piece to be sold away from Leek, but put to a vote the Society accepted £300 for the replica, its viewing supports and a quantity of printed guides. After expenses were paid, each needleworker received £2 5 /6d per share, a share being one yard of embroidery worked. The piece was then put on display at the Reading Town Hall, often in less than ideal viewing conditions.

In 1993, after careful cleaning and modern conservation, the replica was placed in a most attractive purpose-built gallery in the new wing of the Museum of Reading. Care has been taken to educate the viewer as to the subject of the tapestry, and ancillary information, visual guides and artifacts contribute to an atmosphere that enriches the viewing experience. Medieval carpenter’s axes hang by the scenes of the building of William’s fleet, and Anglo-Saxon swords by the battle scenes. As one travels around the gallery sound effects greet the ears — monks chanting, frightened horses neighing, the clangs of metal upon metal, men screaming as they fall in battle. Modern photos of Halley’s Comet, depicted in the panel of the tapestry showing Harold’s crowning, serve to link that distant era with our own.

Conclusion

One hundred and eighteen years have endowed the Leek effort with a patina of its own. There is some differential fading and warping which I believe adds rather than detracts to the embroidery’s appearance. Taken as an emblem of Victorian interest in their Anglo-Saxon forebears it is of signal importance. The fact that a sizeable group of women worked in close collaboration to create and exhibit it and that thousands of viewers paid to see it is testament to how seriously it was taken. The piece demonstrates the pride the Leek Embroidery Society took in the long heritage of quality English needlework and their desire to contribute meaningfully to that tradition. Even their censoring adds historic value to the piece, as it serves to anchor the replica firmly in its own era while harkening back to one of the great turning points in the nation’s history.

If you go:

The Museum of Reading is located in the Reading Town Hall, less than a five minute’s walk from the train station, well served by Thames Trains. Admission is free.

Related Websites:

http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/Chronologia/Lspost11/Bayeux/bay_tama.html shows the entire Bayeux Tapestry.

www.bayeuxtapestry.org.uk is part of the Museum of Reading’s Website, which shows a frame by frame view of the replica.

Suggested reading: Jan Messent The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers’ Story Madeira Threads, 1999

Selected bibliography:

David M Wilson The Bayeux Tapestry Thames & Hudson

Christine Poulson, editor, William Morris on Art and Design Sheffield Academic Press 1996

Michael J Lewis The Gothic Revival Thames & Hudson 2002

The author wishes to thank Jan Messent who generously made available materials concerning the history of the Leek Embroidery Society.